Two months, 200 new ideas and a chance to revolutionize parent engagement in education

For Julie Sepesy, connecting with her children’s teachers has always come easily. She’s that parent who reflexively raises a hand each time a class party needs hosting or a fundraiser needs planning. If she has a question, she reaches out.

But as her two children have made their way through the Fort Cherry public schools near Pittsburgh, Sepesy has met many mothers and fathers who struggle to figure out the parent/teacher relationship. Especially as kids move from the family-centered comfort of elementary school to the fledgling independence of middle and high school, many parents feel disconnected from their kids’ education.

“In the Elementary Center, we all took for granted that we could get a hold of our teachers and there would be constant communication,” Sepesy says. But as kids get older, “we only get communication when things are really, really good or really, really bad.”

And while many parents are unsure what role they can or should play in their school community, educators can find this relationship difficult, too. Historically, it’s been a challenge to get busy parents to engage even when they’re actively invited to participate.

So when Sepesy was invited to lead her community’s team during the Family Engagement Design Sprint launched earlier this year, she jumped at the chance. This two-month creative process, a key part of the larger Parents As Allies initiative, would be all about building on the imperfect but increased communication that began happening between schools and families out of necessity during the pandemic.

BUILDING ON PROGRESS

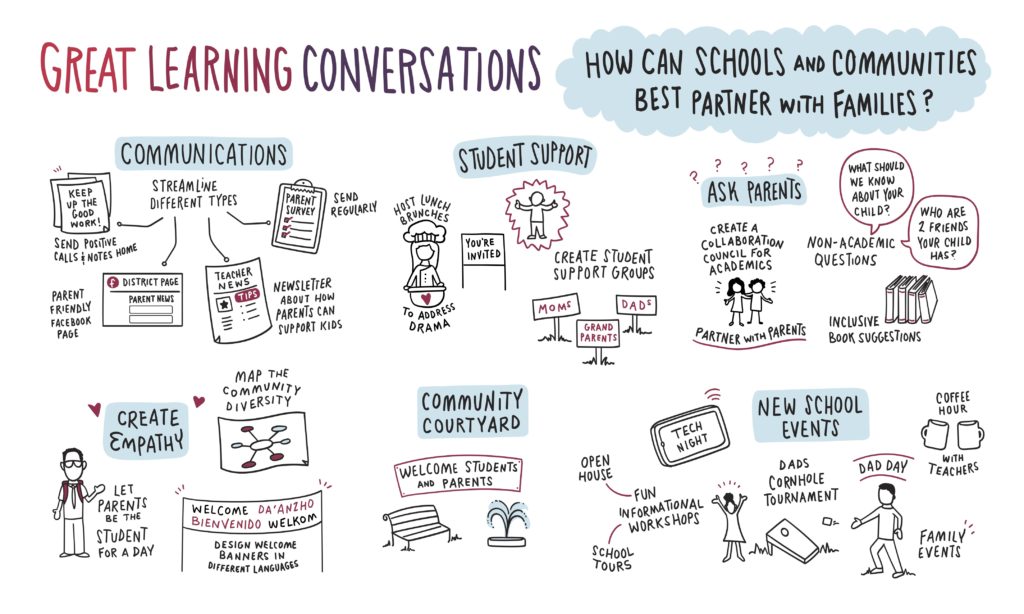

The Family Engagement Design Sprint would be an ambitious project, and yet a realistic one: Rather than trying to create the kind of sweeping overhaul that can take years of effort and never come to fruition, these groups would co-design small but impactful hacks they could implement quickly.

Teachers, school administrators and parents from 11 U.S. communities, as well as Mumbai, British Columbia and the U.K. city of Doncaster, enthusiastically joined the Design Sprint with a common goal.

“Folks came from all over the country — all over the world, frankly — around this central design question of how might we build stronger engagement between families and schools for the benefit of all students,” says Adha Mengis, a program manager at Digital Promise who mentored many of the Design Sprint teams. “We’re all motivated towards designing for the same futures.”

Like Sepesy, Jason Hall also joined a design team in hopes of helping schools and families build better relationships. He came at the process from both sides: Hall serves as principal at New Brighton Elementary School, in a suburb northwest of Pittsburgh, and he’s also a parent in his own district.

Hall has watched teachers and parents struggle to determine where moms — and especially dads — fit in the calculus of a school community. He knew that by improving engagement with fathers and father figures in his district, he could increase family communication while also tackling the rate of discipline referrals among boys in the New Brighton schools.

Like many of the participants, Hall was unfamiliar with the Design Sprint method that they’d be using for the next nine weeks. But it was easy to grasp once the initiative’s organizers — including Mengis, IDEO’s Larry Corio who leads product and impact for The Teachers Guild x School Retool, and Rachel Siegel, a design and innovation specialist based at Lakeland Community College in Ohio — explained how it would work.

The teams each chose one from among five themes identified during research by the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution that included conversations with parents around the world. These five themes were:

- PURPOSE: How might we support schools to better understand parents’ aspirations and motivations for sending their children to school?

- INNOVATIVE PEDAGOGY: How might we boost parents’ comfort with and value of innovative pedagogy?

- AGENCY: How might we build parents’ confidence to engage with teachers and administrators?

- TRUST: How might we encourage schools to build more trusting relationships with families?

- WILLINGNESS: How might we drive parent demand for an education that develops a fuller breadth of skills?

JUMPING IN

At a kickoff meeting in late March, 16 groups of parents and educators learned about these themes and were invited to share their individual identities and strengths — how would they describe themselves and what might they bring to this project? The atmosphere was cheerful and supportive.

Rather than being drained by a year of pandemic-disrupted schooling, many of the 89 participants seemed energized by the chance to share a bit about who they are and how their unique mix of strengths could help their school community.

Some of the participants knew one another (11 of the participating districts, including Avonworth, Brentwood Borough, Butler Area, Duquesne City, Fort Cherry, Hampton Township, Hopewell, Keystone Oaks, New Brighton Area, New Castle and Northgate, are located in western Pennsylvania). But most were meeting for the first time.

Once introductions were made, the groups moved to breakout rooms to choose a specific aspiration statement for their journey. The team from Avonworth chose “to drive parent demand for an education that develops the whole student.” For the group from Mumbai, it was this: “To build parents’ confidence to engage with teachers and administrators.”

Next came the “empathy process,” which lasted about two weeks. Parents conducted empathy-focused interviews with school staff members, while school staff members interviewed parents. This was all about open-ended questions and inviting folks to share stories about their interactions. Beyond chronicling answers, the teams would also notice body language — and allow for silence.

“This was a way to engage directly with communities at a time that’s really crucial to be thinking about new ways to boost engagement for the sake of students,” says Corio.

With help from that increased empathy and knowledge, and with their chosen aspiration as a guiding star, the groups then had about three weeks to brainstorm creative hacks — simple, affordable initiatives that could move the needle toward their goal.

Then, over four weeks of collaboration, they fine-tuned their chosen hacks and prepared to test them in their communities in the months to come.

LEVERAGING THE SCHEDULE

Siegel says the speed of the design sprint process is central to its magic. In the world of education, where change tends to come terribly slowly, it’s especially useful.

“That bias to action makes a difference,“ she says. “It forces a whole different way of approaching challenges.

Hall agrees. He found the process so useful that he soon began applying design thinking to other challenges in his district, like improving professional development programming.

“It kind of forces you to get something done,” he says, because the focus is on testing new ideas and quickly implementing them, rather than waiting until an idea is perfected to even give it a try.

By early April, the groups had begun uploading empathy interview notes to shared Google folders. Some were brief. Others were pages long. Levels of participation did vary across the 16 design teams, but moments of real listening and progress were soon happening in all of these cities and towns around the world.

Educators and parents were approaching this challenge not as opposing stakeholders but as a community in search of connection. They were being challenged to take small risks in search of potentially big returns. The ideas they generated didn’t have to be perfect. They just had to be possible.

UNVEILING THEIR IDEAS

Nine weeks later, modest but potentially groundbreaking initiatives were unveiled at a showcase meeting on May 22 that had parents and educators across the globe applauding each other via Zoom.

In all, 140 empathy interviews had been conducted and 190 small but potentially meaningful hacks were developed.

At Fort Cherry School District, Sepesy’s group is now planning festive get-togethers that aren’t about grades or instruction. They envision a low-key barbecue where educators and families can simply eat and talk. No pressure, just people hanging out together with the opportunity for casual conversations.

Sepesy says it was a powerful experience to have parents talk openly and empathetically with teachers and administrators, and to have those school staff members really talk with and listen to parents.

“That is key,” she says, “because we are all guilty of seeing our own perspective.”

Her district will see how the first get-together goes and then experiment with new variations: Maybe “we’re going to have a chili cook-off, or we’re going to have a hot dog eating contest.” No matter the details, these new gatherings will be all about connecting outside their roles as “parent” and “teacher.”

Meanwhile, Hall’s team in New Brighton had dreamed up “A Boy, A Ball, A Gym, A Man.” It’s a program where fathers or father-figures will bring the boy they’re raising to the school gym on a weekday evening or Saturday morning to help him learn to shoot baskets. While talking (and, likely, laughing) about how tough it can be to make a basketball land in a hoop, they’ll also casually talk about things like commitment, fight-or-flight responses and the role of friends and family in their lives.

While the boys get social-emotional support, the fathers and father-figures will be developing a connection to the school. Hopefully, they’ll build a growing sense that it’s a place where they belong and can valuably contribute. This will all happen with resources that the community already has — the elementary school’s gym and its sports equipment. There is no cost.

Across the world in India, Shindewadi Mumbai Public School will be pursuing their own hacks: Arranging Wellbeing Calls to students to see how they’re doing not just as learners, but as people. They also plan to invite parents to observe classes, demystifying the school experience and helping caregivers feel welcome.

Each community had tackled the same larger challenge and used the same design system, but they developed bespoke approaches worth trying before this malleable moment in history passes.

At the final showcase, Siegel, Corio and Mengis praised the teams for their effort and their faith in the process.

“Parents and administrators just jumped in and said, ‘Sure, I’ll help with these teams. I will come to these sessions. I will be the coach, the motivator, the inspirer, the organizer, the texter or emailer, or the trainer,” Siegel told the group. “You said ‘yes’ to this experience. And so here we are.”

Mengis agreed: “I didn’t do this on purpose,” he said, smiling. “But my hoodie says ‘Trust the process.’ And I feel like everybody in this Zoom room really did.”