Parents as Allies: Designing for family engagement, globally and locally

Story by Peter Worth of The Teachers Guild x School Retool.

“Without the parents on this team, we wouldn’t be able to truly make a difference in what parent engagement will look like.” — school administrator, Pennsylvania, about the Parents as Allies design sprint

We often talk about parent and family involvement in school — parents and caregivers working to help with homework, attend school events, volunteer time, and support in all sorts of ways from home. The need for schools and families to engage each other is nothing new. But what would it look like to involve families in the life of schools in a way that truly centers families’ hopes and needs for their children’s learning? What might we learn if parent involvement was integrated from the ground up, and what if change was led by families, themselves?

These aren’t new questions, but they have been elevated over the last two years as the relationship between schools and families has been forced to change. The pandemic has disrupted schooling, leaving families around the world to engage with schools in different ways. They have taken on responsibilities for teaching and supporting learning, and have gained perspectives and insights on the school experience — all while navigating health crises, employment challenges, and loss. The reopening of schools became a crucial moment for the school-family relationship, and an opportunity to strengthen it in the service of students.

“I discovered that to strengthen family-school relationships, school communities need… to find a way to bridge the gap amongst [their] members. We need to lay the building blocks of our future by putting processes in place to allow students, parents and teachers to become a cohesive unit. Please note for us to be successful in this endeavor, some assembly is required.” — Kristina Campbell, parent, Pennsylvania

A design process to reimagine engagement

In March 2021, a collective called “Parents as Allies”was formed to support families and schools in this moment. With the support of the Grable Foundation, an innovative consortium of organizations — including Kidsburgh, the Brookings Institution, IDEO, and HundrED — joined together to identify, share, and facilitate the use of promising new strategies to build stronger family-school partnerships on a local and global scale. In this context, The Teachers Guild x School Retool team at IDEO held a two-month design sprint to explore the question: How might we build stronger engagement between families and schools for the benefit of all students?

Through the sprint, The Teachers Guild x School Retool wanted to help families leverage the tools of community-centered co-design, including the Co-Designing Schools Toolkit, to develop and strengthen their creative confidence and ability to engage with their children’s education.

Sixteen design teams with an interest in family engagement were recruited in communities in Canada, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All together, nearly 80 team members, most of them parents, guardians, or family representatives, signed up to begin working for change in their school communities.

Seeking confidence to engage

Teams ranged from three to six members, often led or co-led by a parent, with at least one school representative to support families and ensure sustainability. Team Leads came together across distance and time zones for training, coaching, support, and reflection at key points during the process.

They started by articulating an aspiration — their north star to guide the design sprint. Most of the school-family partnership teams chose an aspiration that reflected the trepidation that families can often experience when dealing with their children’s school.

“We are going to build parents’ confidence to engage with teachers and administrators.” — Example of team aspiration

With an aspiration in place, the teams conducted over 100 empathy interviews and surveys to learn deeply about the experiences and needs of the members of their school communities. They then brainstormed over 190 ideas, or hacks, that would allow them to take action immediately, with existing resources, to get started. During the design sprint, the families, teachers and leaders, as well as The Teachers Guild x School Retool team began to see some initial themes emerging about how to support effective co-design in the context of a family-school challenge.

Building relationships was a key starting point

A design sprint can be a logistical challenge in the best of times, let alone during the last few months of a busy school year. Bringing together busy families at the height of a pandemic adds another level of complexity, but also creates opportunities for urgent, authentic collaboration. It’s key to start by spending time really getting to know and understand each other.

For parent and team lead Julie Sepesy and the team from Fort Cherry School District in Pennsylvania, that understanding meant empathy surveys — a lot of them. This team, which self-identified as a diverse and creative team of taskmasters, surveyed 58 stakeholders in their school community, and saw how much parents and teachers in the district value human relationships.

“I discovered that to strengthen family-school relationships, school communities need…to get together face-to-face more in a fun and festive setting — to get to know each other and feel that they can work as a partner for the success of the students.” — Julie Sepesy, parent, Pennsylvania

“Fort Cherry is a small school district…where people know and care about each other…I have observed parents helping other families, working together for the kids’ benefit and watching children who aren’t theirs — caring for others. I am proud of our district,” said a parent. “I chose to take on this role to get to know more of our older students on a personal level,” said a teacher who had taken on an extracurricular role outside their grade level.

Through their interviews, they heard parents, teachers, and administrators express concern about a lack of opportunities to really get to know one another as people, to build those relationships they valued, which would form the bedrock for collaboration. They also saw a difference across families in their expectations about what they would get from school.

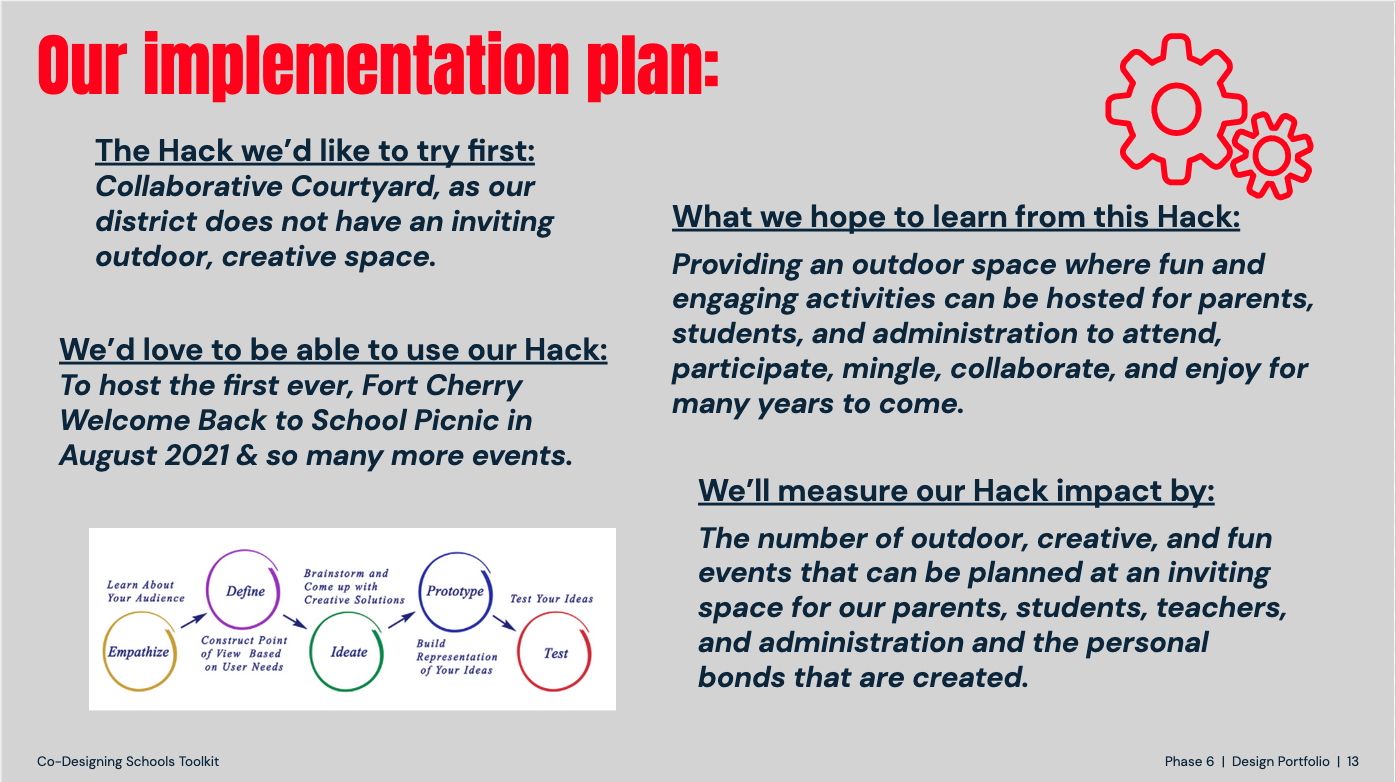

Out of these insights, the Fort Cherry team designed a set of easy-to-implement hacks to build relationships and confidence. They created a plan for designing a multi-use community courtyard from an existing space. They scoped a variety of new school events, including pairing informational workshops — such as parent education and a STEM family night — with movies in the courtyard, a back-to-school picnic, and a talent show.

Across the board, design teams noticed that establishing relationships before moving to solutions could lead to the co-design of solutions that really address community needs. A design team of fathers from New Brighton Area, Pennsylvania was looking for ways to engage men in their community to get more involved in school life. When their empathy work revealed that some men found the school a welcoming place, but “some parents struggle to even walk into a school building, let alone have quality conversations with school staff,” they started with relationships. Their first hack? A cornhole tournament — each dad invites another dad to the tournament, and while there, they recruit and get feedback on their plan to increase engagement. As one parent and teacher put it, “I discovered that to strengthen family-school relationships, school communities need to find ways to decrease parents’ apprehension about getting involved.”

Focusing on the whole child and using an equity lens gave a clearer picture

From Canada’s Central Okanagan to Mumbai to Pittsburgh, design teams found that the families and schools in their communities shared a strong focus and commitment to the future of their children. They want all students to be “successful, thriving members of society,” they expressed that “kids are the number one priority,” and that “everyone wants kids to be seen as whole humans and for them to grow up to be good people.”

“The social-emotional wellbeing of a student is as important as the academic part.” — kindergarten teacher, Pennsylvania

What emerged strongly from the empathy phase of the design process was that family engagement could play a key role, and also that schools could go further in ensuring that families, especially those from communities that have been marginalized, are welcomed and empowered to participate.

Alongside that was an acknowledgment that schools have work to do to make all families feel equally welcome in the school, but they also had a foundation of trust in their child’s education and wellbeing.

The design team from the Akanksha Foundation (LFE) at Shindewadi Mumbai Public School in India, led by administrator Abhishek Chavan, completed this challenge at a time when India was at a crisis stage in the pandemic. However, they were committed to completing the design sprint and continued to meet, often virtually or by phone, and sometimes late into the night. From their empathy research, they determined that the school and parents had a foundation of trust. Moving forward, they determined to center equity in their work: “My team came to know the importance of equity and they wanted to bring this thought into the community engagement goal of the school for the coming year,” one member said.

This emphasis was echoed in other teams: an equity lens was an essential tool in making good on the commitment to improve student well-being and nurture the whole child. One school concluded that the task of providing a culturally competent curriculum relies on the willingness of teachers and parents, since it’s not in the core curriculum. Another designed a hack to map their community based on languages spoken at home, culture, race, ethnicities, and birth countries.

For the Akanksha Foundation team, the first action was to design a process for well-being calls and a circle of trust. Every teacher and administrative staff member in the school will take turns so that each 7th Grade student receives a check-in call twice a month during the pandemic. From those calls, the team intends to learn how they can more strongly support the physical and emotional needs of the school community.

Parent leaders thrive with clear pathways and consistent support, not just titles

Shifting the nature of family engagement in schools is not an overnight process. Just saying that design teams will be led by parents and identifying someone as the leader could overlook a history or culture that render these efforts non-starters. A mindset shift is often required by both schools and families to work in a new way, with new roles and power dynamics. The design sprint process helped to provide the clear pathways, structures, and consistent support that set up parent leaders for success.

“Parents and families know and trust that the school body as a whole will help their children succeed. Now it’s making sure we communicate with them every step of the way and show them that their involvement matters, that they matter!” — Cassandra Pencek, school leader, Pennsylvania

The sprint process started with the creation of the design teams. Every participating school community received suggested criteria for recruiting an amazing design team:

- Representative identities: Recruit a team whose backgrounds — racial, ethnic, socioeconomic — are representative of your community, and target members from groups that have been marginalized

- Roles: Create as much variety as possible to avoid groupthink

- Archetypes: Who are the Community Connectors, Questioners, Idea Generators, Builders, Ambassadors, Strategic Thinkers?

For the design team leads, additional guidance was suggested that leads satisfy as many of the following criteria as possible:

- Represent a perspective that has been historically marginalized (or focused on elevating these voices)

- Parent or parent advocate

- Well-networked in the community

- Not in a formal leadership role (to avoid perpetuating power dynamics)

Once selected, design leads received training and coaching in specific aspects of design leadership. Experienced design coaches Adha Mengis and Rachel Siegel met with the design leads periodically throughout the two months. They introduced tools and activities from the Co-Designing Schools Toolkit, and helped the design leads experience first the process they would later facilitate as team leaders. Resources were designed for wide-spread use with commonly used and freely downloadable digital tools, so that participants had access to everything the coaches did.

Adha and Rachel also “got meta” to maximize access. They were transparent about their own design of the coaching sessions, explaining their “why” and even giving participants a matching agenda template structured to engage a group’s emotions from the start, generate ideas and understanding, and then move to action, so that design leads could feel comfortable putting the tools to work immediately. As one parent said, “During empathy, I learned how to solve any school-related issue using the process that I have experienced during all the meetings.”

Parent Tamika Lipka led the Butler Area School District design team in Western Pennsylvania, which included two principals. Very aware of how titles and structures can sometimes be used to create distance between families and schools, Tamika and the team designed a series of hacks to make families, in all of their diversity, feel more welcome. Their design included three separate support groups — for grandparents, moms, and dads — each with a different name and focus. They also took a look at the very name “PTA” (or “Parent Teacher Association”) and decided to rebrand it as the “Parents as Allies Team,” honoring the strength and contribution of families to the school community and to their children’s education.

Translating learning into action

The family members and educators who participated in this design sprint stepped up to explore ways to strengthen the school-family connection in the service of students. In the words of one leader: “We do not need to have everything figured out. That will come in time. It is important to try something.” Over the summer and as the new school year began, the design teams implemented their hacks, reflected on their learning, and planned new hacks.

The Akanksha Foundation team adapted the training structure used by Adha and Rachel and trained a group of parents in leading family wellness calls, grounded in social and emotional learning. The parent leader team connected with 30 families. Through their calls, the parents listened to other parents, provided social emotional support, and even offered guidance on receiving COVID vaccination, a priority for the school. Abhishek saw a shift in how the parents engaged with him, now that they weren’t being treated as “parents only.” They call on a regular basis now, and are working with the school as a team. “We have a bond,” he said. “Now I have a team supporting me…helping school be a better place for our students.”

In New Brighton, where Jason Hall and the team were focused on increasing engagement of fathers in the school community, they began by expanding the group, inviting more dads to participate and apply their skills. Some worked on event planning. Others co-designed a logo. Sometimes, they found, parents are a little afraid to come into the school building, but you just have to ask, and once they feel they have common ground, they identified fathers feeling more comfortable to talk with others. Leaning into the lever of space, they are designing activities that use the gymnasium and conversation starter cards, offering dads a place and structure to bond with their children.

The Butler Area School District team developed a series of parent engagement activities, which they shared on a rack card sent home to families at the beginning of the year. When principal Cassandra Pencek heard from parents that they were hanging the cards on their refrigerators, they knew the message was getting out. In one activity, a Great Learning Conversation held in conjunction with Kidsburgh, 40 families from the two schools came together to share their hopes and dreams through conversation and activities. The activity concluded, Cassandra said, “by making sure families know that we want to really work together, and we want to know any needs, and we want to be here for the academic component, but so much more than that.”

The impact was not limited to the school design teams. Rachel Siegel, who co-facilitated the sprint, found an opportunity to adapt the toolkit and approach to work with parents, teachers, and administrators at the district level. With the support of the superintendent, Rachel and her colleague facilitated five design teams in a radical collaboration approach to improve parent engagement. They met at a community college, with parents working together in blended teams across different perspectives. They started with constructivist listening, first understanding one another and their shared purpose and goals for students. Then, they dug into the design work together creating simple, manageable ways to impact students. The parents left inspired by the positivity of the process and the relationships that were developed, and grateful to have other parents and teachers who wanted to create change to support students. As one parent reflected, “this is the beginning of us coming together as a community.” It is just the beginning; in addition to most of the parents and educators signing up for another design cycle, the Board of Education members were so inspired by the design teams that they want to join, too.

Moving forward

The work the teams started in the family design sprint continues. From their experience have emerged some considerations, or perhaps reminders, that may help as we continue to apply co-design to the work of building strong family-school experiences:

Invest time and energy in building authentic relationships as a key starting point (and maybe end goal, too): Across design teams, parents and leaders found the human connection essential to their school-based work, but also a powerful outcome of the work. How might we approach family-school engagement from a place of true relationship building first?

Honor the realities and challenges of families’ and educators’ real lives: It is an understatement to say that this is a challenging time for schools and families. How might we design for family engagement that eases rather than exacerbates those challenges?

Create the space to invite parents in, supporting them in taking on new roles: The parents in this challenge were glad to be asked to join as leads and meaningful contributors. They also sometimes needed support or training to engage with the school in a new way. How might we encourage and support the full school community to participate?

Adapt the tools and processes of co-design to your community’s needs: In this challenge, school teams used the Co-Designing Schools Toolkit. Once they had used the kit a first time with a facilitator and were familiar, they adapted the processes to suit their context and projects. How might we design for adaptability and remain flexible in our approach to family engagement?

While these considerations may sound familiar, and are resonant with recommendations for Collective Impact and other community development efforts, they can also be easy to forget or breeze past amid the complexity and busyness of the lives of schools. We offer them here for potential reflection and inspiration. As we collectively continue this work, how might we build on these lessons to help schools and families leverage their combined potential to support students?

Want to know more about Parents as Allies? Learn about the research revealed in the Brookings Playbook, hear how the local Hi Neighbor! event brought people together, discover the HundrED Parental Engagement Spotlight report and find much more information here.