How local parents and teachers feel about ‘Maus’ being banned — and about teaching difficult history

It is a familiar story, repeated so many times in American life over the decades: Words and pictures, simple and powerful, and divisive once again.

A rural Tennessee school district’s recent decision to remove a graphic novel about the Nazi Holocaust from its eighth-grade curriculum has reverberated throughout the nation. In many communities, including ours, it’s prompting conversations about censorship, book banning and the appropriateness of teaching true history to children.

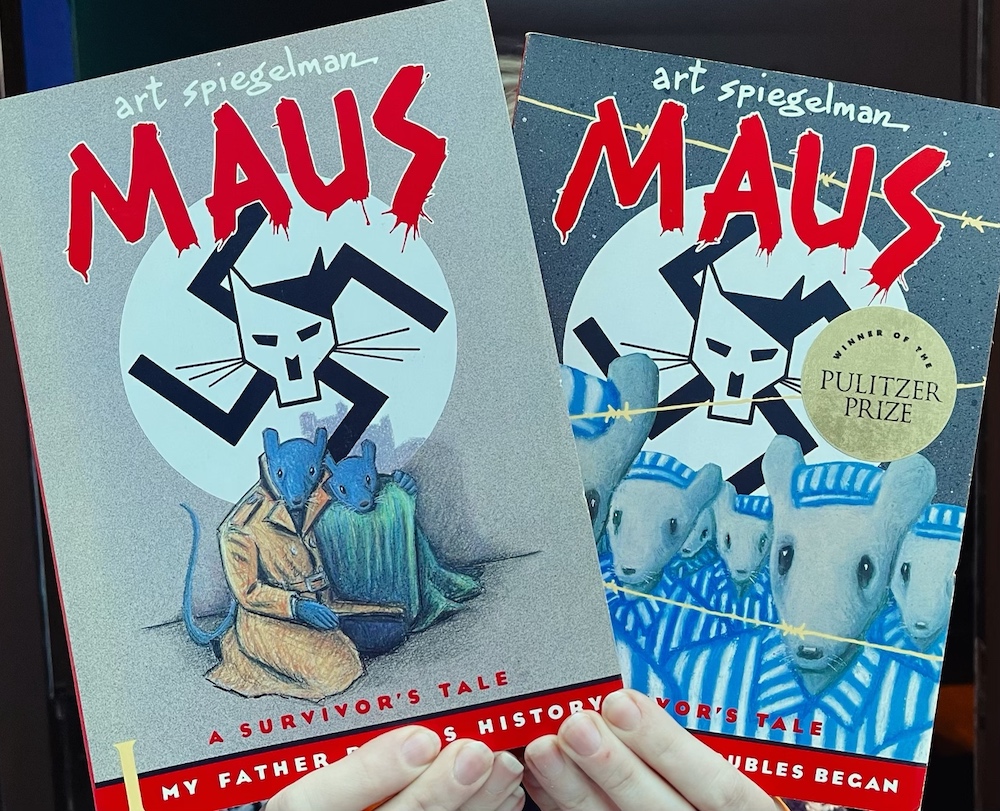

You may have heard about it. If not, here’s what’s happened: The McMinn County Board of Education in Tennessee voted unanimously in January to ban Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus.” The book, which shows the different groups as anthropomorphized animals — the Germans are cats, the Jews mice — chronicles Spiegelman’s parents’ experiences of anti-Semitism in the 1940s and their internment at the Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz, Poland.

According to the school board meeting’s minutes posted online, objections included “rough, objectionable language,” and a drawing of a nude woman in the book. “It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy,” one board member asked, while another said: “We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history…. We can tell them exactly what happened, but we don’t need all the nakedness and all the other stuff.”

In Aspinwall, Tina Tuminella remembers reading “Night,” Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel’s harrowing account of surviving Nazi concentration camps, in ninth grade. Today, she’s the mother of two young children. Tuminella’s son, Theo DeLong, learned about the Holocaust last year, in third grade at O’Hara Elementary School.

“I am very happy he was exposed to ‘Number the Stars,'” Tuminella said, referring to Lois Lowry’s historical fiction about Jews in Copenhagen, Denmark, during World War II. “It’s just not direct, it’s very subtle, but I can tell you, from attending the Zoom meetings, that kids are aware of this in the third grade. Reading ‘Night’ is when it occurred to me, but my kids are exposed to it much earlier. That is progress — that he knows of it. They can handle some of these concepts.”

KIDS AND COMPASSION

“The kids are very interested in this topic,” said Jessica Resek, a gifted support teacher who has taught Lowry’s novel at O’Hara Elementary School for five years. “It is amazing that it’s third-graders who remind me it’s National Holocaust Remembrance Day.”

While the students also learn about teenager Anne Frank, who died in a Nazi concentration camp after hiding for two years with her family in a secret annex in a house in Amsterdam, Resek avoids getting into the specifics of where exactly the Franks — or, other Jews — were taken.

“I have to tread very lightly there,” she said. “They know the Jews are being removed from Copenhagen in ‘Number the Stars,’ they know the German soldiers are coming to taking them away, but not necessarily where. They know Anne Frank died from illness.”

But she and the students still took virtual tours of the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam so they could see where Anne and her family hid.

Sometimes, Resek has to confront what actually happens in real-time, she said. In 2018, as she was preparing to teach “Number the Stars,” she and her students had to confront the shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue that killed 11 people.

What the students were learning at school suddenly “became very real to them,” Resek said. “It really hit home to them. For some, it was their synagogue.”

But when she discusses the themes and story of “Number the Stars,” Resek concentrates on the evils of prejudice and discrimination, and the bravery of the characters in saving Jewish families.

“We talk about how the main character had to be brave and stand up to the German soldiers, and how you never know when you may be called on to be brave,” she said.

TEACHING AT HOME

Becca Tobe also has two children at O’Hara Elementary. They have not read about the Holocaust in school yet. But they are aware of it because the family discusses it at home: “We think it’s important they know what happened,” Tobe said. “And it’s amazingly important it is taught at the school district. The Holocaust is an important topic to introduce.”

Tobe said she and her husband give their children “a little bit of information and let it sit,” waiting to see what questions the children have — why were Jewish people targeted, why is there hatred, or were children hurt in the Holocaust?

“We say there were kids who were affected by the Holocaust,” Tobe said. “We always answer the questions with an honest answer because it’s important for them, as Jewish children, to know what’s happened in the past.”

Banning books serves little purpose, Tuminella said, because it only persuades people to go look for the prohibited material.

“The minute you list what’s forbidden fruit, it only makes the kid want it that much more,” she said. “Overall, I find it ineffective and silly … I hope it backfires.”

Since the Tennessee school board’s ruling, “Maus” has soared onto the bestseller list again. Comic book stores have offered free copies to students. One store started a crowdfunding page and easily surpassed its goal of $20,000. They’ve already raised more than $100,000. An Episcopal church in Tennessee offered discussions of the book, and a professor in North Carolina offered online lectures to eight-grade and high school students about the book.

For Tuminella, removing “Maus” — and banning books, in general, from school libraries and curricula — “reflects more on the adults,” she said. “It is not protecting the interests of children. It’s about sharing our fears. I feel we are going backwards. We’ve done that, we’ve been there.”

Tobe believes children should be exposed to the horrors of the Holocaust and racism. Otherwise, they might not understand how hatred affects other people.

She recounted an experience her niece once had as a middle school student in the Fox Chapel Area School District: The girl was on the school bus when a fellow student asked aloud who the Jews were on the bus, Tobe said. Some raised their hands, and the other student said: “You should all go back to the gas chamber.”

Another reason Tobe wants her children to know about the Holocaust is to “want them to be proud of being Jewish,” she said. “We don’t want them to be scared to be Jewish. We want them to be appreciative of the lives they have.”

“It’s important for them to understand their history and their past, that such hatred existed,” Tobe added, “so they can stand up for other minorities when it’s aimed at them. We want them to be upstanders, not bystanders.”

Resek agreed: “They should learn about the dangers of prejudice and discrimination, and the importance of human respect and that there are some people willing to stick up for it,” she said. “It teaches them to be strong leaders.”