Assemble’s Afro-futurism curriculum is looking to a remarkable past to chart a better, more equitable future

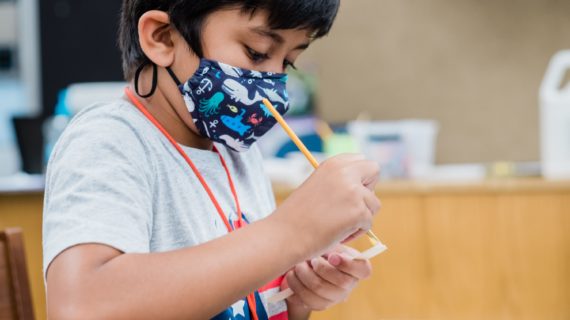

Photo above by Ben Filio for Remake Learning. To discover more about the Remake Learning network, click here.

The community learning hub Assemble is a place where ideas grow. In this fertile space, conversations spark projects and some of those projects get brought to life in remarkable ways.

Usually, it’s kids who do this creating. But Assemble’s spirit of experimentation also inspires the adults to break new ground. That’s what happened back in 2019 when Ja’Sonta Roberts spoke with Assemble’s executive director Nina Barbuto about the importance of representation.

Roberts was a relatively new employee at Assemble back then. But she’d recognized a gap in the curriculum: Amid so much creative STEAM learning, no one was talking about the many Black artists, engineers, mathematicians, and technologists who have helped shape history around the world.

Let’s fix that, Barbuto replied. So Roberts began exploring the ways Black creators have made history and the ways their ideas can be built upon in the future.

“She had given me this full autonomy,” Roberts remembers. Suddenly, “we were building a new learning track.”

Less than three years later, Assemble’s Afro-futurism curriculum is enlightening a growing community of students at K-12 schools and out-of-school-time programs around the Pittsburgh region. Soon, it’s going to reach even more students through an innovative program to bring teaching artists into schools.

Starting Small, Then Blooming Big

In the fall of 2019, Roberts launched the earliest iteration of the Afro-futurism curriculum at Westinghouse High School. She began with a group of just five students. But word soon spread.

Within just a few months, this afterschool group had grown to 25 students, all eager to merge hands-on STEAM learning with a deeper understanding of Black history.

“We saw how much the students wanted to talk about these things. There isn’t a space in your traditional academic settings to really talk about culture and race with the sciences, the math, the English and the arts,” Roberts says. “Having this open space where not only are we sharing information with them, and giving them examples, but we gave them room to breathe it in and discuss it freely… it became a safe space to talk about it. That is the foundation of how we approach this with all of our other partners.”

Soon Roberts and her team at Assemble were proposing an Afro-futurism workshop for Pittsburgh Public Schools’ Summer Boost program. “Sure enough, they accepted it,” she says. “I got many emails talking about how this was something they’d been looking for.”

The program was even modified to make it available for primary-age students, further expanding the audience for Afro-futurism. It has only snowballed since then.

The curriculum is now in use for elective classes at the Urban Academy and Arsenal Middle School. Also, Assemble offered professional development for teachers at Propel Schools, so they are now teaching the curriculum at all their locations.

And soon, the curriculum will make another leap forward: The Arts Ed Collaborative’s Teaching Artist Substitute Initiative has Afro-futurism as one of many creative pieces of curriculum at their disposal when the program launches later this semester.

“Arts Ed Collaborative (AEC) is excited to include a small slice of Assemble’s Afrofuturism Curriculum in a new Field Guide for teaching artists working as substitute teachers,” says executive director Yael Silk. “AEC also hopes that more schools learn about Afro-futurism by checking out Assemble’s profile on artlook® SWPA and engage in powerful partnerships in the coming years.”

AEC’s Field Guide allows teaching artists to choose lessons and creative projects to suit the age group they’ll be teaching and the particular school where they’ll be substituting.

With a resource like the Afro-futurism curriculum, these artists arrive at a school “ready to deploy,” says Barbuto. Even though they’re working in an unfamiliar space with kids they haven’t met previously, resources from Assemble and others helps ensure that their time in the classroom is impactful.

It’s this kind of partnership – creative curriculum from an out-of-school-time provider, taught in K-12 schools by teaching arts from throughout the community – that expands the power of southwestern Pennsylvania’s learning ecosystem.

As each new semester begins, these collaborations grow.

“I definitely see more examples of good partnerships or budding partnerships between OST and schools,” says Stephanie Lewis, director of relationships at Remake Learning. “My hope is that momentum will continue – not just between the OST partners and schools, but also with other nonprofits.”

Looking Ahead to a Stronger Community

Afro-futurism is built on the Ghanaian concept of “sankofa.” Like the sankofa bird, you have to look back before you can effectively move forward. So this curriculum combines STEAM learning and innovating with “learning about the many people who have been erased from our history books,” Barbuto says.

This is vital for Black and brown students, because “if you don’t see it, you don’t believe that these are fields in which people of color contributed, which is a complete falsity,” Roberts says. But she points out that it’s vital for all students to learn this information. Today’s white students will be among tomorrow’s voters and parents and teachers shaping America’s communities.

The history of the African diaspora “is a part of our history as humans in the world,” Roberts says. “We can’t deny contributions, because it’s creating a false sense of what society is and that’s not what we want for our children.”

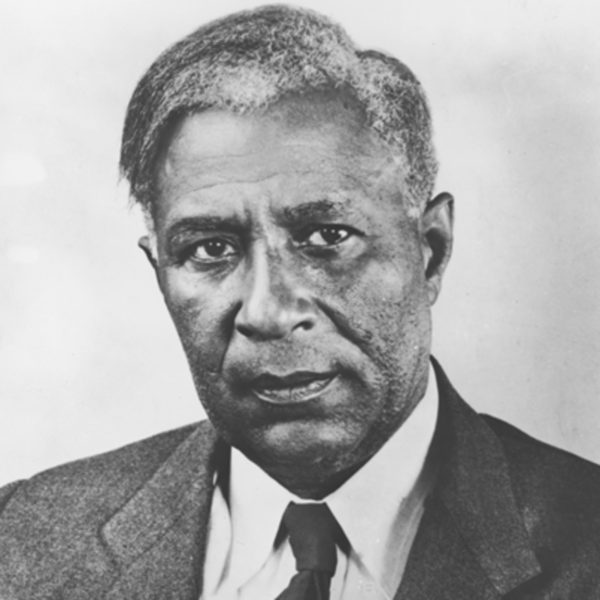

One of Barbuto’s favorite examples is Garrett Morgan, the Black journalist, entrepreneur and inventor who patented the first traffic light with a warning signal between stop and go. Most students, whether they are Black or white, haven’t been taught about Morgan.

But his role in American history is enormous: Prior to his invention, traffic lights were simply red and green. Vehicles sometimes crashed because one light would turn red at the same moment that the opposing light turned green.

Morgan saved countless lives by realizing that there needed to be a third signal (what eventually became the yellow light) in between and engineering a new traffic light design.

In the spirit of Afro-futurism, Assemble’s curriculum explores that history and then looks to the future, giving kids a hands-on opportunity to imagine what kinds of traffic lights they might design – perhaps for use with driverless cars in the future.

“What can we speculate on and imagine?” Barbuto asks. “You’re not just designing and creating something for today, but maybe for 20 years from now.”

Black Joy, Celebrated By All

One morning Roberts saw this multicultural learning in action when she taught an Afro-futurism class about Jean-Michael Basquiat, who used elements of physics and biology in his art.

The class was a half-day camp for primary schoolers at Environmental Charter School. As the students filed into the room, one boy stood out.

“He was so excited. He was so antsy in line. He couldn’t wait. He just immediately rose his hand and said, ‘We’re gonna learn Basquiat today, aren’t we?’”

Roberts watched as he dropped his book bag and threw his jacket off to show her the Basquiat sweatshirt he’d proudly worn to school.

“Of course, I gave him a chance to share with the rest of the group,” Roberts says. “What did he know about Basquiat? He was just ecstatic to share that he was a painter, that he was from New York, that he was African American. And he couldn’t really say ‘neo-expressionism,’ but he really did try hard and it was the cutest thing.”

Here’s what struck Roberts most: He was not a student of color.

“That goes to show us that these biases and these things that we try on as adults are things that are taught when we’re children. He just saw that this was an amazing artist that he was excited to learn more about, and he was African American. The boy knew that,” she says. “It was about what he did, not what he looked like. And he created that normalcy.”

Want to learn more about the work of Remake Learning? Check out these stories.