Deeper connections: Brookings brings data (and encouragement) to Pittsburgh families and schools

Photo above by Ben Filio.

On a chilly morning as the holiday school break approached, a crowd of parents, teachers and school administrators filled the event space at Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center. On tap for the daylong workshop: a deep, eye-opening dive into the latest research on family-school engagement — and a chance to learn from one another.

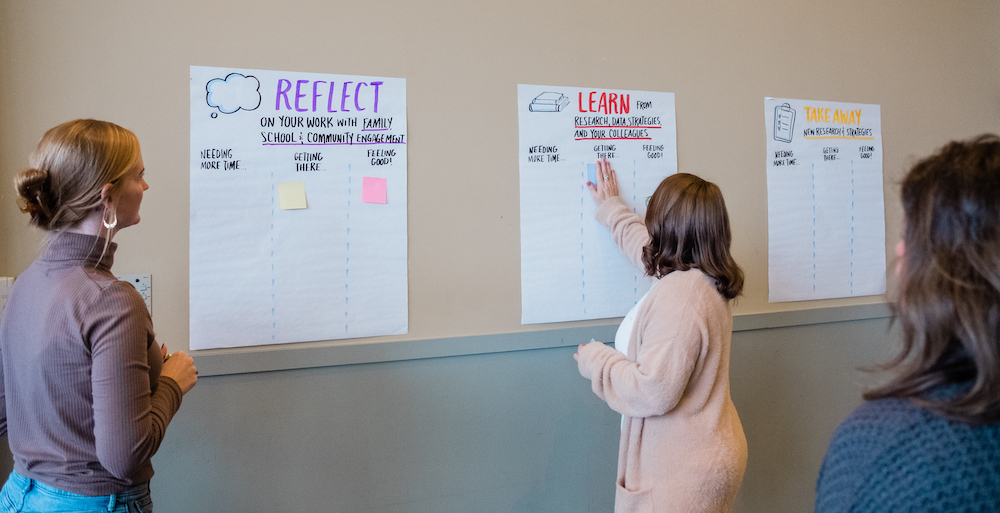

Their morning began, though, with a chance for each participant to look inward. They reflected on their own thoughts and asked themselves a powerful question: What do you really want school to be like for kids?

Those opening moments of reflection at this Parents as Allies gathering set the tone for a day filled with hopeful discussions about the dozens of creative initiatives that are beginning to bridge gaps between schools and families throughout the Pittsburgh region. The workshop was hosted by Kidsburgh and researchers from the Brookings Institution’s Center for Universal Education (CUE) on Dec. 12.

There was plenty of honest talk about the barriers communities have faced in their efforts to help schools and families trust and connect with each other. Fortunately, this creative group was also able to share updates on the hacks they’ve been using to build that vital trust.

SHARING PROGRESS

Since Parents as Allies 2.0 launched last spring, 22 school district teams of educators and parents have been using human-centered design to tackle all kinds of things in more creative ways.

Along the way, their work has been informed by global research findings from the CUE team. They’ve used eye-opening data about the beliefs parents and educators around the world have about the purpose of school. And there have been surprising findings about how common it is for each group to misunderstand the priorities of the other.

As detailed in CUE’s comprehensive playbook, “Transforming Education Through Family-School Collaboration,” parents and schools have rarely talked with each other about what they actually want schooling to accomplish. Is school purely a place for academics? Is it meant to train for the best possible job? Or is school designed to help us learn to be good citizens, or become people with the social and emotional skills to get along with others and navigate the highs and lows that life throws at all of us? Until the pandemic, relatively few people were thinking like this.

Brookings found that throughout the world, many parents and schools see social-emotional learning as a key purpose of school. Yet many people in each group told researchers they believe the other group mainly cares about academics.

The CUE team walked attendees through this research. To extend this learning beyond the current Parents as Allies 2.0 participants, the event was open to organizations that help children and to any parent who wanted to learn more about this groundbreaking work.

Teams from several districts also spoke from the stage during panel discussions, while others chimed in from their seats to speak honestly about the challenge of this important work. People spoke about transportation issues, communication issues and the challenge of planning events that parents will have time to attend. They also spoke about the apprehension and lack of trust many parents feel when they’re asked to come to school.

But resoundingly, the message was this: These challenges can be hacked. And when schools reach out in new ways, parents respond.

Ambridge Middle School Principal Ronnell Heard told the audience about the logistical challenges of holding events for families.

First, the middle school and high school in Heard’s district are located far apart in a community with little public transportation available, and some families in the district don’t have cars. So events hosted at the middle school are difficult for many families to reach, but most can access the high school’s downtown location.

Second, school events that focus on academics draw few visitors. Athletic events bring a bigger turnout, and that sparked a great idea: The annual high school football game between Ambridge and Aliquippa is the biggest football game of the year. What if the school district hosted a social event there, so parents could get to know teachers outside of any academic context?

Heard’s people went all out. They hired a DJ and set up a space for dancing, put out cornhole boards and invited a parent who owns a food truck to set up at the event. The goal: to encourage parents and educators to communicate, as Heard puts it, “like regular people.”

“It’s not the discipline conversations about what your kid’s not doing, what your kid needs to work on. It’s just a really comfortable space that involves food and a really good time,” Heard told the crowd.

In the days after the event, parent feedback was strong. “When can we do more?” Heard and his team remembered parents saying. And: “This was an amazing opportunity for us to come out and just talk to you guys. I brought my wife, I brought my son.”

It’s a formula the other 21 school districts in attendance can emulate: Meet people where they are with no agenda other than socializing.

“Now, you know, parents call me: ‘Hey, Mr. Heard, how you doing?’ And I’m like, ‘Great. How are you doing?’ ‘Oh, great. Can I come up?’ ‘Absolutely.’ So a lot of people really are engaged. They’re really excited about the next event that we’ll have.”

The project “Parents as Allies” is generously funded by The Grable Foundation.