Can the Westinghouse Castle find a new purpose as an arts center and school?

This article first appeared at NEXTpittsburgh.com, a media partner of Kidsburgh. Sign up here for NEXTpittsburgh’s free newsletter filled with all the latest news about the people driving change in our city and the innovative and cool things happening here. Photo above by Mike Machosky.

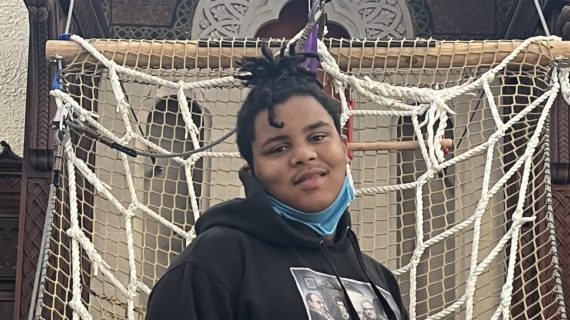

Across the parking lot from Westinghouse Arts Academy, a stone castle strongly resembling Hogwarts looms over Wilmerding. And if all goes as planned over the next three or four years, the charter school’s 9th-graders may get to finish their high school education in classrooms inside Westinghouse Castle.

A group of investors, led by developer Bill Malloy of Greensburg, is working to raise the estimated $10 million to restore the stately Romanesque building.

“I can’t think of any other building that looks like it, with those huge stones and the giant clock tower,” says Richard Fosbrink, the school’s CEO. “Inside there’s so many beautiful, paneled offices and board rooms with big fireplaces, and big executive dining rooms. Architecturally, there’s a lot of cool spaces.”

The castle, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has been vacant for several years. Officially the former Westinghouse Air Brake general office building on Commerce Street, it was built in 1890 by George Westinghouse and constructed by architect Frederick Osterling. A fire partially destroyed Westinghouse Castle in 1896, but it was rebuilt that year and then expanded in 1927, says Fosbrink.

A new nonprofit, Turtle Creek Valley Arts, will sublet most of the building to the high school for arts-based education and use it during non-school hours for community events. Fosbrink, executive director of Turtle Creek Valley Arts, credits Bill Malloy, managing partner of the developer, Westinghouse Castle LP, and Wilmerding Mayor Gregory Jakub with shepherding the project to bring the castle back from near ruin.

“We’ve got some very dedicated initial investors, five or six people, who are getting things rolling,” he says. “And we’re talking with other foundations to gauge their support and looking at other ways to raise the money.”

In 2016, Priory Hospitality Group President and CEO John Graf had hoped to convert Westinghouse castle into a 40-bedroom, destination resort known as The Castle Hotel after buying it at a sheriff’s sale. Graf told the Pittsburgh Business Times last year that the pandemic had limited his prospects for funding it.

At a recent “light-up night” event to announce the new plan for the castle, Fosbrink talked with state Sen. Jim Brewster about securing Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program money and other governmental resources. He envisions using all four floors for a mix of classrooms and labs for both traditional arts and digital arts programs — pottery, painting, music and dance studios, computer and science labs, as well as TV and photography studios.

The top floor would be devoted to a new culinary arts program for students during the day and community members at night. They could make use of those majestic dining and conference rooms, a ground-floor cafeteria and a commercial kitchen.

But first, most of the building’s walls, flooring and mechanical systems will need to be replaced. Rain and snow collapsed ceilings and damaged plaster and wood, although the steel superstructure is strong and some floors were tiled with terrazzo.

Fosbrink hopes to get the first floor ready for use by the start of the next school year.

“It’s a huge project,” he acknowledges. “The building’s been empty for at least a decade and there’s significant damage where the flat roofs failed. When it was raining outside, there was water running down the steps of the center staircase. But those roofs have just been replaced.”

Malloy was instrumental in getting the charter school up and running, says Fosbrink. The building initially housed Westinghouse Memorial High School, and then became an elementary school for East Allegheny School District. But it had been empty for a decade before its restoration.

Westinghouse Arts Academy was established in 2017 and has grown from 70 students in its first year to 320 students currently. The building can accommodate 550 students, but with 30 percent growth in each of the past few years, Fosbrink anticipates needing the castle soon. The school is tuition-free for students in grades 9 through 12, who come from 32 Western Pennsylvania districts.

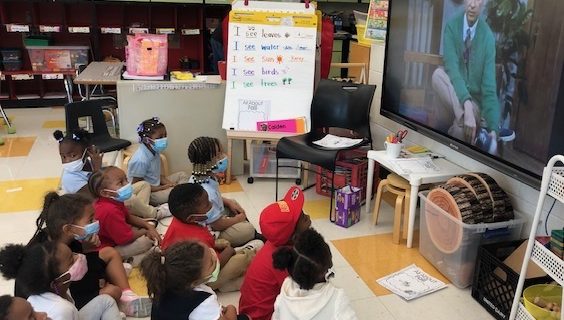

“There is a demand for [arts-based education],” Fosbrink says. “We’ve seen over the past few years that school districts are making tough choices to eliminate arts programs. The need definitely exists.”

Students audition or present portfolios to attend the academy and once accepted can choose the focus of their art. Their days are a mix of academic classes — math, science, history, languages — and arts programming such as music, dance, theater, literary arts and studio arts.

Fosbrink came here from Chicago, where he ran a national nonprofit. He was with the Theatre Historical Society of America in Pittsburgh before agreeing to head the academy. He holds degrees in music education, fine arts and arts management, and started his career as a high school music and theater teacher.

He’s eager to keep the school growing at its rapid rate and to develop Turtle Creek Valley Arts for the community.

“I’m kind of a unicorn for this job,” he says of the castle’s revival. “It’s going to take at least three to four years, but they’ve started a lot of the work.”