Freeman Family Farm is boosting Manchester one crop at a time

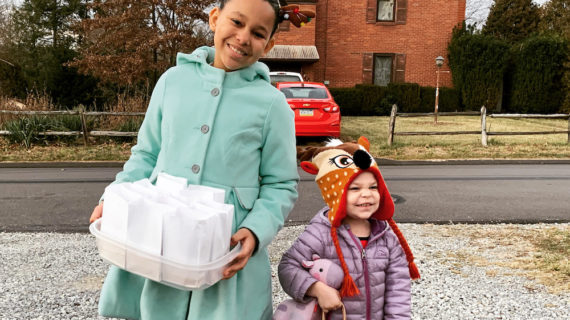

This article first appeared at NEXTpittsburgh.com, a media partner of Kidsburgh. Sign up here for NEXTpittsburgh’s free newsletter filled with all the latest news about the people driving change in our city and the innovative and cool things happening here. Photo above courtesy of Lisa Freeman.

In a city where many predominantly Black neighborhoods don’t have access to a grocery store, a Black-owned farm in Manchester is providing food to the community while planning to open a market next spring.

The Freeman Family Farm and Greenhouse started as a school and community garden in 2011. The 10,000-square-foot property includes a hen house, vegetable garden, and plum, apple, peach and pear trees.

In June, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced that it is partnering with the Reinvestment Fund to provide $970,000 to improve access to healthy foods in underserved communities in Pennsylvania. The Freeman Family Farm received a $175,000 grant from the program.

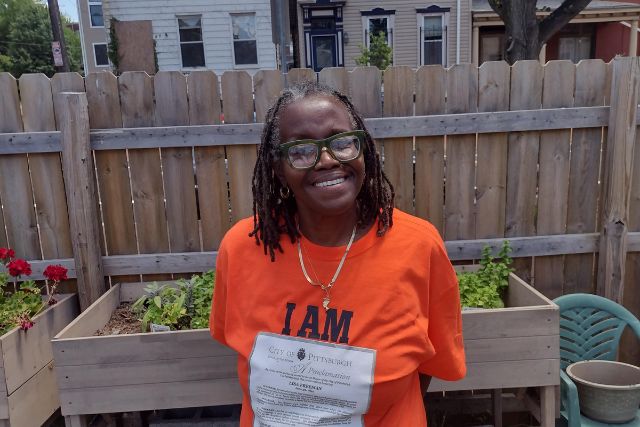

Owner Lisa Freeman, who spent more than 35 years as a service worker, uses her experience to provide food for an underserved and marginalized community. After buying a condemned home in the city and renovating it with her now-deceased husband, Freeman started her farming journey after creating a community garden for her son’s school.

“My son went into school, one of the poorest schools in the Pittsburgh Public Schools District, Manchester Elementary,” says Freeman. “They had a plot of land right outside their school, and I said, ‘OK, I’m going to do community school gardens, and that’s going to be an outdoor learning space,’ and that is what thrust me into the limelight of being a gardener.”

Freeman ran the school community garden for five years, and she later helped build it into a small social service project working with area nonprofits. Former Pittsburgh Mayor Luke Ravenstahl gave a proclamation to Freeman on June 30, 2012, celebrating her work in the community.

“I am proud of being a part of Black history,” Freeman says. “I’m very proud of what we’ve done.”

According to a 2020 study from Carnegie Mellon University, historically Black neighborhoods like the Hill District and Homewood suffer from a higher percentage of food insecurity and redlining — a discriminatory practice in which mortgage lenders or insurance providers restrict services to certain areas of a community, often resulting in some neighborhoods becoming food deserts.

Freeman Family Farm not only helps Manchester residents deal with food insecurity but also teaches neighbors about gardening. The farm also offers a work-release program where incarcerated men can work on the farm.

“The men brought barbecue and cooked out for the kids and had a nice lunch with them, but some kids were crying, which was very emotional,” says Freeman. “And after the fact, we realized that a lot of the kids’ parents, their mother or father, were incarcerated, so that hit a sore spot with those kids.”

Despite the farm’s role in the neighborhood, Freeman had to scale back during the height of the pandemic. Though she had originally aimed to open the grocery store sooner, Freeman says she hopes to be open by May 2023. The market will be one more step forward in building up her neighborhood. It’s all about people helping each other at the local level, she says, not a big developer coming in and changing things.

“You have to keep the money circulating within your own community to build up your community,” says Freeman. “And as many small businesses grow and are able to see things happening, that is how you revive your community.”