Here’s the secret to happy, successful kids. Pittsburgh experts weigh in.

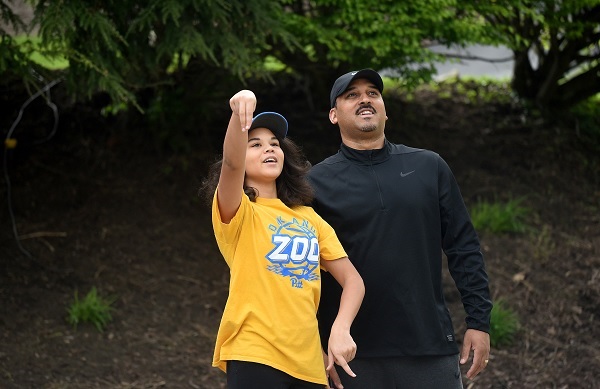

Photo: Sanaa Brown, 12, follows through on a shot while playing basketball with her father. Photo by Philip G. Pavely.

From the time children are born, parents pay close attention to their physical health. There’s an emphasis on nutritious meals, medical checkups, exercise and the importance of a good night’s sleep.

But sometimes a child’s mental health can be overlooked.

“It’s one of those things that’s not as obvious,” says Dr. Bradley Stein, a child psychiatrist and senior physician policy researcher at the RAND Corporation. “Parents are not as attentive to it. Other times we misinterpret what we’re seeing. Sometimes when kids are really struggling psychologically, they may be more likely to throw a tantrum or talk back or yell, just not behave as well as they normally do.”

While mental health can be taken for granted, its importance, especially among children, is paramount. Just like healthy meals or exercise, maintaining and paying attention to a child’s mental health is essential.

The building block to success

“The ability to manage emotions is the building block for all other aspects of life,” says Dr. Elizabeth Reitz, a licensed psychologist and owner of Strong Foundations Psychological Associates in Mt. Lebanon.

“Children do better in school and have stronger relationships with others when they are skilled at recognizing their emotions and know strategies to effectively regulate their mood,” she says. “For instance, being able to manage frustration well will allow children to persist even when schoolwork or sports get hard.”

That mental and emotional balance helps kids be resilient, confident and primed for success.

“Kids who are feeling emotionally stable, happy and able to cope are better able to learn and be creative,” adds Dr. Elizabeth Miller, director of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

“Happier minds also mean healthier bodies – stronger immune systems and growth,” she says. “Kids who are feeling supported, connected, and loved are also able to explore and interact with their environments. It’s on us adults to help create environments in which all children can thrive.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines mental disorders among kids “as serious changes in the way children typically learn, behave, or handle their emotions, causing distress and problems getting through the day.”

The diagnoses for children from 3 to 17 years range from behavioral problems (7.4 percent) to anxiety (7.1 percent) to depression (3.2 percent).

Recognizing when a child may be having a problem is predicated on recognizing normal behavior. All children will act out. All kids, just like all adults, have good and bad days.

According to Stein, unusual behavior that lasts for a couple of weeks could be a sign that a child is having difficulty. Self-isolation, non-engagement, and shying away from activities they normally enjoy may indicate that a child is wrestling with an emotional problem.

“Parents know their kids best, so when behavior changes, that is the signal to parents that something may be wrong,” Stein says.

It’s OK to be not OK

The good news is that there’s an increasing awareness of the importance of kids’ mental health. Mental health is no longer a secondary issue among educators and health professionals, Miller says, and the traditional stigmas have mostly been eliminated. The message is: It’s OK not to be OK. Resources are available to provide help when needed.

“The last decade has seen a remarkable shift in openness in terms of talking about mental and emotional health, and recognizing these needs are absolutely fundamental to a child’s overall health and an ability to thrive and succeed,” Miller says.

“We have seen an increased understanding of the importance of mental health services,” she says. “Pediatricians, schools, and out-of-school programs are increasingly recognizing the value of supporting a child or young person’s mental health as part of the work that we do.”

Communication

One of the most important things parents can do to monitor their kids’ mental health is to simply talk to them. Conversations – whether during meals or study breaks at home, or even during trips to the grocery stores for essentials – offer insights into a child’s well-being.

While the traditional dinner table is a prime opportunity for interaction, Stein acknowledges that doesn’t work for every family.

“Other families have to find different opportunities,” he says, “but the underlying point, the important one here, is to be able to have opportunities to have those conversations with our kids, and to be able to have them open up and understand what is going on their lives, both when things are going well and when they’re struggling with things.”

Communication can take alternative forms. Reitz says that digital conversations via apps like FaceTime can be useful when parents and children are separated.

“I’ve also had some success with families having journals back and forth between parent and child, where I might leave you a note of encouragement or a thought about something I had,” Reitz says, “and the child’s invited to reciprocate that, too. Sometimes writing can be a good way to communicate. It doesn’t feel quite as intense.”

Resiliency under pressure

Kids have long endured bullying and peer pressure. The rise of social media and the impact of the coronavirus outbreak have added to the stress levels of some children.

But kids also possess a quality that helps them cope with the stresses and pressures of school, friendships, and even the pandemic: resiliency.

“They have strengths and the ability to bounce back,” Miller says. “That’s really vitally important. We need to support parents, schools and others who work with young people to know how to build skills in resiliency. These are skills that everybody can learn: How to cope when you’re feeling stressed. What skills to use when you’re feeling anxious. How do you reach out to somebody when you’re feeling a little lonely and isolated and even depressed?

“Those are skills, frankly, that everybody should have,” she says. “We should all be working on building those skills because they are learned skills.”

How to help your kids develop good mental health

It’s essential to be proactive about your child’s mental health. Here are tips recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that will help foster social and emotional health.

- Catch your kids being good. Praise them often for even small accomplishments like playing nicely with brothers or sisters, helping to pick up toys, waiting for their turn or being a good sport.

- Find ways to play with your kids that you both enjoy every day. Include some type of regular physical activity, such as a walk or bike ride around the neighborhood.

- Read with your kids every day. Turn off the TV before dinner and have conversations with kids at the table. After baths, read books with your kids in preparation for bedtime. This routine will help them to settle down and sleep well.

- Limit screen time to no more than two hours daily for kids ages 2 and older. The AAP does not recommend any screen time for those younger than 2 years of age. Never put a TV in a child’s bedroom. Parents should watch along with older children and try to put the right spin on what they are viewing. Young children should not be exposed to violence on TV, including on the news.

- Make time for a routine that includes the family talking about their day together. Take turns sharing the best and not-so-good parts of the day.

- Provide regular bedtime routines to promote healthy sleep. This time of day can become an oasis of calm and togetherness in the day for parents and children.

- Model behaviors that you want to see in your kids. Parents are the first and most important teachers. What you do can be much more important than what you say.

- Set limits for your kids around safety, regard for others and household rules that are important to you. Ask others to respect your rules.

- Be consistent with limits for your child. If you must enforce a rule, do so with supportive understanding. Don’t give in, but do quickly forgive. Do not hold a grudge for past mistakes. Encourage learning from mistakes so that they do not happen again.

This story is part of the Kidsburgh Mental Health Series, funded by a grant from the Staunton Farm Foundation. The Foundation is dedicated to improving the lives of people who live with mental illness and/or substance use disorders. The Foundation’s vision is to invest in a future where behavioral health is understood, supported, and accepted.

Other stories in the series include the Kidsburgh Mental Health Survey report, insight as to how parents can deal with coronavirus anxiety, and advice on remaining resilient during times that try your family’s mental health. Also, a fascinating look at the teenage brain and Anchorpoint Counseling Ministry’s hugely successful fundraiser.