5 family-friendly tips for frank discussions on positive racial identity

Lingaire Njie’s Pittsburgh upbringing was filled with positive messages about her family’s race and heritage. In her Afro-centric household, she was taught to celebrate her racial identity. Still, when asked her first memory about race, she had to admit it was negative.

She remembers being teased for how dark her skin was. Even though her parents told her how beautiful her skin was well before the teasing began, it was the taunting that stuck.

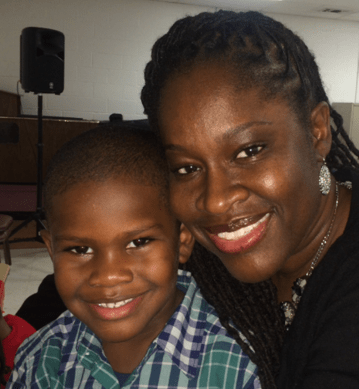

“I know how fortunate I was to grow up in the family I grew up in,” she says, and makes a point of carrying on the same positive reinforcement with her 5-year-old son, Jibril Bailey-El. Yet “there are so many subtle things in our society that are constantly working in opposition to positive racial identity.”

Njie, a member of the family and youth engagement team for the superintendent’s office of Pittsburgh Public Schools, was among a panel of parent volunteers interviewed for a recent report from the University of Pittsburgh Office of Childhood Development. The Race and Early Childhood Collaborative issued the report last month titled “Understanding PRIDE in Pittsburgh: Positive Racial Identity Development in Early Education.”

Kidsburgh interviewed a number of professionals involved with the study for tips on how best to foster a healthy understanding of race, racial identity and racial awareness, starting at home. Here’s what they had to say:

Kids notice race. “They pick that up, whether they are white or black,” says Aisha White, director of Ready Freddy: Pathways to Kindergarten Success at the University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development. If you don’t want your children to have biases or negative feelings about their race, “then you do need to have intentional conversations to help them understand it.” That can mean talking about historic and geographic origins, explaining why some people have dark skin, some have lighter skin and what parts of the world their ancestors came from.

Keep information factual, without judgment. White says to avoid attaching value to the information shared with children. As is the case with teaching children about gender differences, they should receive accurate, not watered-down or overly filtered information, which can lead to, at the very least, confusion. “You can’t talk until you know what to say,” she says, so make a point of understanding what your message is going to be.

Read about it, together. Books can be excellent portals for understanding race, researchers say. “They are looking to us for guidance but they don’t know how to bring it up appropriately,” says Medina Jackson, community outreach coordinator for the Ready Freddy program. Books, along with other media, can give children the avenues to broach subjects they otherwise aren’t able to address. Jackson suggests finding resources that address skin and eye color, celebrate triumphs in diverse groups of people, discuss challenges facing racial groups and also simply reflect everyday life. Appropriate titles for preschoolers include “We’re Different, We’re the Same” by Bobbi Kates and “Black is Brown is Tan” by Arnold Adoff.

Reflect within. Jackson also suggests parents spend some time reflecting on their own racial identity and awareness, for it will greatly inform the ways they engage with their children. For better or worse, “we carry those experiences with us,” she says. Once adults are aware of the experiences that shaped and molded their own sense of race, they can also be more comfortable in talking about it with their children.

Seek additional resources. “Look for resources and information to better understand the general landscape of race in America,” Jackson says. Resources include the video the Office of Child Development created to break down the findings from its report. Appendix G of the written report includes a recommended reading list for parents and practitioners.

Many generations have assumed that children benefit from a colorblind approach to address racial identity in a healthy, positive manner. For a time, it seemed appropriate to not draw attention to racial differences, or race in general, but the report shows otherwise.

“Colorblindness—I think the problem with it is it implies erasure,” Jackson says. “It doesn’t acknowledge who people are.”

The report’s results focus largely on the ways that school systems, classrooms, teachers and public organizations can better engage children ages 3 to 6 in understanding race, be it theirs or others. Among these suggestions was a need for increased partnerships between schools and professional organizations, all in the effort to close what remains a significant performance gap in minority children’s test scores.

Perhaps most importantly, the report called for more direct communication with children about race, and for a more collaborative approach between families and classrooms in fostering healthy racial identities.

As a parent, Njie says she is thrilled to see research addressing race in early childhood education, but remains sure that the most important work needs to be done at home. By age 4, her son had already picked up on issues concerning police brutality and race, though her family is deeply conscious that age-appropriate discussions take place in his presence.

“I feel we have the primary responsibility to cultivate a positive racial identity,” she says. “I want you to see my color. I don’t want it to dictate how you treat me, how you interact with me.”

“There’s a lot of value in people’s differences,” she says.