In Hampton Township, schools are teaching for tomorrow while staying true to their history

This story is one in a series created in collaboration with the AASA Learning 2025 Alliance to celebrate the work of groundbreaking school districts in the Pittsburgh region. Kidsburgh will share these stories throughout 2023.

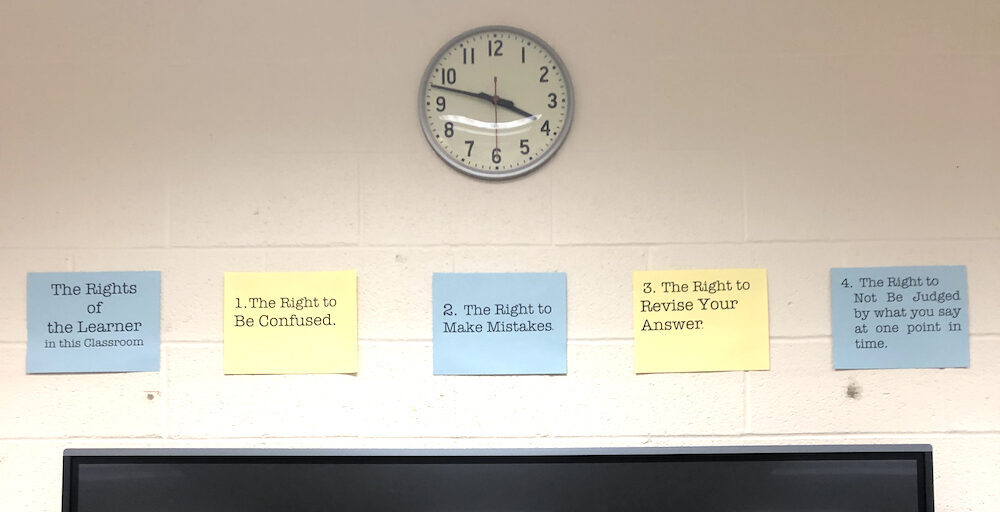

Across one wall in Amy Leya’s math classroom at Hampton High School, signs printed in the district’s blue and gold proclaim “The Rights of the Learner” – freedoms that students in many public schools are rarely granted. They include:

- the right to be confused;

- the right to make mistakes;

- the right to revise your answer;

- the right not to be judged by what you say initially.

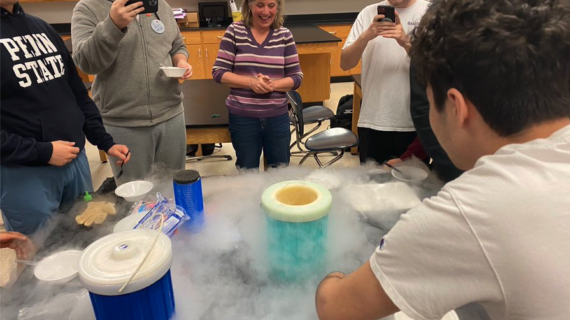

Leya’s message is clear. You’ve come here to learn geometry or algebra, but you’ll leave with skills applicable everywhere, including perseverance, critical thinking, and collaboration.

“I’m teaching math, but you can transfer that to your entire life. Jobs, relationships, everything you do,” Leya says. “Take your time, make mistakes, learn and grow. To me, that’s the learner’s mindset. That’s perseverance. That’s critical thinking.”

This plays out in a range of ways – including her policy of “not graded yet.” Often, teachers hand back assignments with incorrect questions marked. But even if the teacher adds a note about where things went wrong, “that paper is either going in the recycling bin or going into their folder,” Leya says. “It’s been graded. So the student is done with it.”

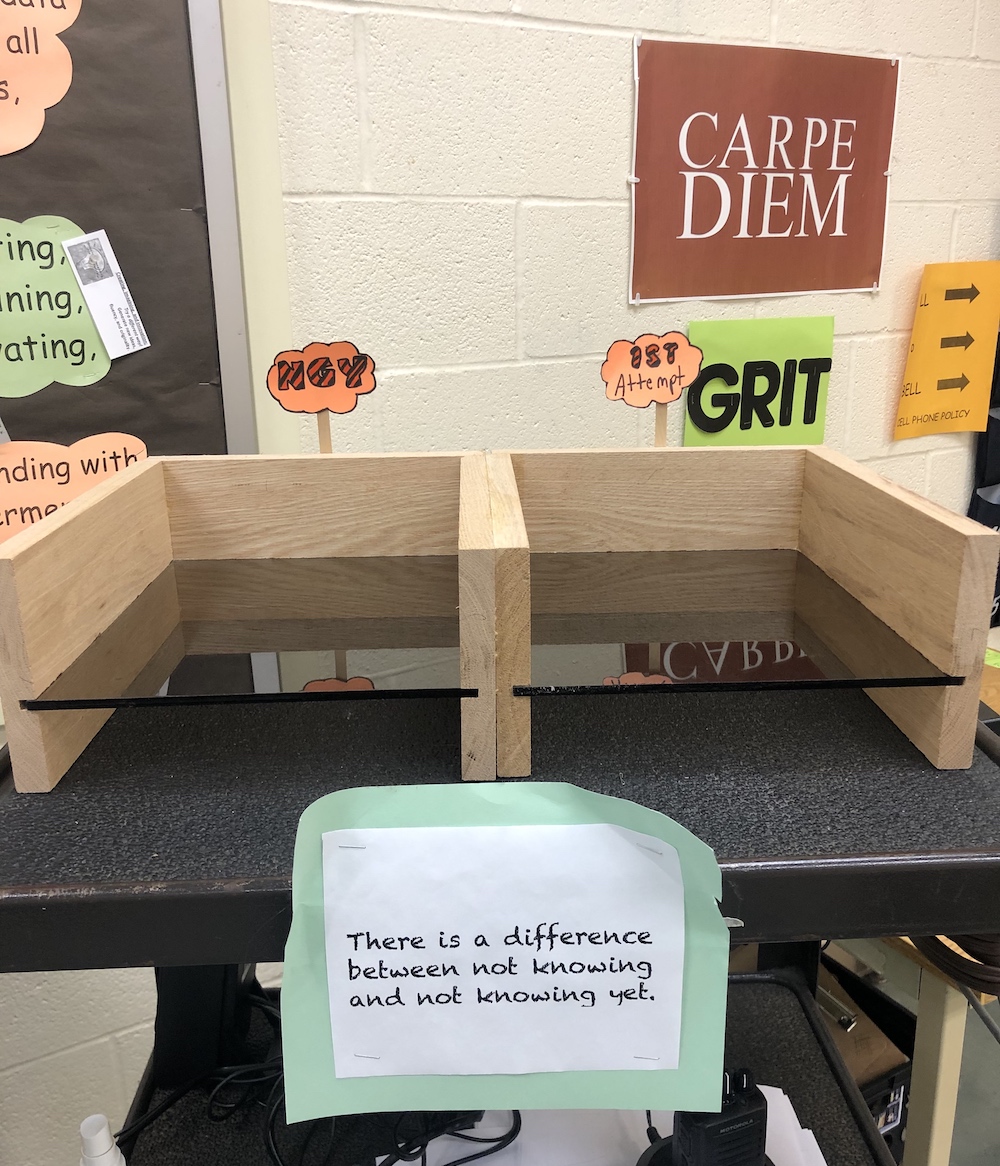

While seeking a better method, she discovered “not graded yet” (NGY). Today, her students drop work in a box labeled “First Attempt.” Beneath it, this message is posted: “There is a difference between not knowing and not knowing yet.”

If the work is returned labeled NGY, students tackle it again – multiple times, if necessary. They stick with it, learning along the way.

PAINTING THE BEST PORTRAIT

Educators and policymakers speak often about “21st-century skills.” In response, many school districts are spelling out their “portrait of a graduate,” isolating the skills and mindsets students need to succeed in our complex world.

At Hampton, the district’s “Portrait of a Talbot” (a “talbot” being the school’s mascot, a hunting dog that roamed Europe in the 17th century) is based not just on the latest learning innovation. It is rooted in a mindset taught at Hampton since Leya herself was a student there in the 1980s.

Work on the Portrait of a Talbot began in February 2022. In surveys and brainstorming sessions, teachers spoke about critical thinking’s importance in our misinformation-saturated world. Students described inspiring experiences, like a career-exploration class that one called “the most engaged and thought-promoting thing I have ever done.”

The district also consulted with the nonprofit Battelle For Kids and discussed portrait creation with other districts in the Western Pennsylvania Learning 2025 Alliance, a regional cohort of school districts working together to create student-centered, equity-focused, future-driven schools. Led by local superintendents and by AASA, The School Superintendents Association, it gives districts like Hampton a chance to workshop ideas with local and national peers.

“We’ve asked our teachers, administrators, community members, and our students – what are the core key competencies and dispositions we want our kids to have for life outside of Hampton?” says the district’s superintendent, Dr. Michael Loughead.

Through that process, he says, the district developed six pillars – communication, collaboration, critical thinking, a learner’s mindset, empathy, and perseverance – that reflect the skills that universities like Carnegie Mellon and key regional employers say they’re seeking.

“It’s so powerful,” Loughead says. “We’re just able now to talk with more passion about what the tradition of excellence really means.”

LOOKING AHEAD WHILE STAYING TRUE

Even before work began on the Portrait of a Talbot, district teachers had been working to build those skills – and build them early.

When Hampton first-graders begin their “How Can We Light our Way in the Dark?” science module, they get a black screen, a base strip, and a flashlight. Shining a flashlight at the base strip, they look through three different materials (clear plastic, parchment paper, and black card stock). They record observations and ask: “What happens when you put something in a beam of light?” The kids make claims based on data, state those claims to the class, and cite evidence.

This is science learning. It’s also collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and the beginnings of the “learner’s mindset.” Removcik’s team has begun documenting examples like this to discover how the district’s curriculum already teaches these skills.

“We want our teachers to be able to share some practices they’re already using that speak to these competencies,” Removcik says. Also on tap: a K-to-12 team will identify these competencies across different grade bands.

In her classes, Leya finds students eager to work on these skills. They don’t balk at sticking with a problem, she says; instead, they see an opportunity.

“I have never gotten a negative response from a student about giving them another attempt,” Leya says. “I’ve done surveys and the kids say, ‘You’re allowing me to learn from my mistakes,’ ‘You actually forced me to learn it and I felt safe to make mistakes.’”

Not far from a sign in Leya’s classroom that reads “Carpe Diem,” students see one more powerful message – perhaps Leya’s favorite. It’s a bright green sign stating in bold block letters, “GRIT.”

A couple of years ago, several students were so inspired by this sign and what it evokes that they came to her with an idea: Get custom rings made for themselves and for Mrs. Leya, engraved with that one powerful word.

“So we have our GRIT rings,” she says. “And they have this skill. They know they can stick with things. They know they can solve problems. It’s not just an idea to them. They own it.”

Want to download this story? Click here for a PDF.