Kidsburgh Hero: Dr. Betty Robinson

In the late 1950s, when Pittsburgh Public Schools hired Betty Robinson to teach at Beltzhoover Elementary, a woman from the school board pulled her aside. “You understand,” the woman told Robinson, “that you’re the first Negro to teach at Beltzhoover. If you don’t succeed, there won’t be any others.”

Thus began Dr. Robinson’s career in Pittsburgh. And given her legacy — which today includes a beloved charter school and legions of students spanning four generations — to say she succeeded would be an understatement.

“Teaching is all I ever wanted to do,” says Robinson, who is 88. “When I was little, and my teachers asked me what I wanted to be, I always said, ‘I’m going to teach.’ Meanwhile, there wasn’t a black teacher probably in the state of Pennsylvania. It was just unheard of. But no one ever told me I couldn’t do it.”

For more than 50 years, Dr. Robinson worked to give Pittsburgh’s kids that same sense of possibility.

In 1968, as cities across the country grappled with the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, Pittsburgh’s Manchester neighborhood was placed under martial law. To give children a safe haven, Robinson and her husband — the Reverend Jimmy Joe Robinson — established the Manchester Youth Development Center in an old plumbing warehouse. As the Center took shape, Robinson canvassed the neighborhood, asking parents what they wanted for their kids.

Nearly all their answers were the same, she says. “They wanted their children to read better than [the parents] could themselves.”

Robinson responded by launching one of the first after-school programs in the country. With donated materials and little money, she quit her job at Pittsburgh Public Schools, where she’d been promoted to principal, and devoted herself to the program. A decade later, she went a step further and opened a private nursery school that, over time, expanded to include older grades. Taking no salary, Robinson used any available resources to cover costs for families who couldn’t pay tuition. In 1998, the school received one of the region’s first charters and became Manchester Academic Charter School (MACS).

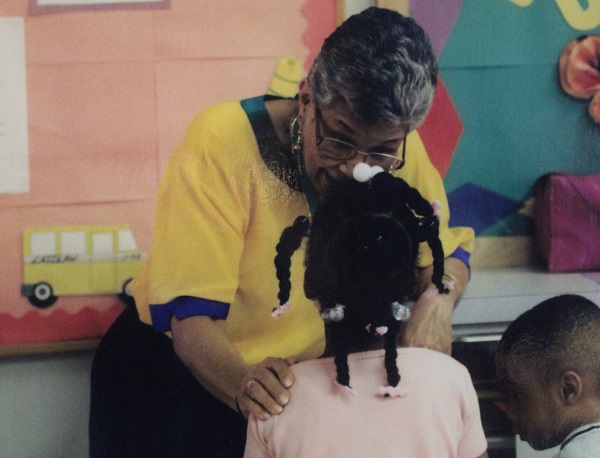

Today, MACS serves nearly 400 students from kindergarten through eighth grade. Parents sing its praises, and its staff includes several of Robinson’s former students. And though she’s officially retired, her presence still looms large: Robinson’s great-grandchildren attend the school, and nearly everyone in Manchester knows her as “Gram” — the neighborhood’s tireless matriarch.

“I’ve been here for about 17 years,” says Vasilios Scoumis, the school’s CEO. “But I haven’t replaced Gram — I’ve embraced her. She’s one of the most influential people in my life, and she’s always there for us when we need her.”

The school celebrates its 20th anniversary this year, with big plans on the horizon, says Scoumis. Its middle school is slated to move into the renovated Allegheny branch of the Carnegie Library, where it will share space with the world-renowned Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh. And as the school grows and expands its programming, it will also honor its roots — students will commemorate the Robinsons throughout Black History Month.

It’s a fitting tribute to two local legends. In addition to being the first black football player at the University of Pittsburgh, Rev. Jimmy Joe Robinson marched with Dr. King in Selma and spent decades as a leading civil rights organizer. And Gram’s a pioneer in her own right, breaking down barriers at Beltzhoover and elsewhere — though she tends to downplay her courage. “I wasn’t trying to break down anything,” she says. “I just wanted to teach.”

To the people close to her, this comes as no surprise.

“With Gram, it’s kids first. Always,” says Larry Berger, head of The Saturday Light Brigade and a MACS board member. “She’s a gifted teacher with a brilliant mind, and she looks at every single thing through the lens of what’s best for kids. She’s relentlessly focused on that — I’m not sure I’ve ever met anybody whose focus is that strong and that sharp.”

Her husband agrees. “She’s always been like this,” says Rev. Robinson, laughing. “She never takes credit for what she’s done.”

The teacher who changed the lives of so many simply shrugs it off. “I don’t need credit!” she says. “The Lord got me started. And the children keep me going.”