Mid-Atlantic Mothers’ Milk Bank is making donor milk more accessible to babies — and researchers

It’s been a big year for the Pittsburgh-based Mid-Atlantic Mothers’ Milk Bank, which is celebrating its fourth anniversary. Not only have they opened a new research biobank, but they’ve also influenced legislation at the state level. The efforts focus on improving healthy outcomes for our smallest neighbors in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and beyond.

Here’s some background on this remarkable story:

Growing scientific evidence shows that breast milk provides more than just nutrition. This dynamic “superfood” is said to have anti-inflammatory and immunological benefits, particularly for preterm babies and other medically fragile infants.

“Human milk is very complex with many different components facilitating a healthy microbiome and immune system,” says Denise O’Connor, founder and executive director of the Mid-Atlantic Mothers’ Milk Bank (formerly the Three Rivers Mothers’ Milk Bank).

Timothy Hand, Ph.D., an assistant professor at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the Pitt’s School of Medicine, studies the infant intestinal microbiome and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), an inflammation of the intestine. Now he is learning more about how breast milk can protect infants from NEC, thanks to the Human Milk Research Institute and Biobank, a new initiative of the milk bank.

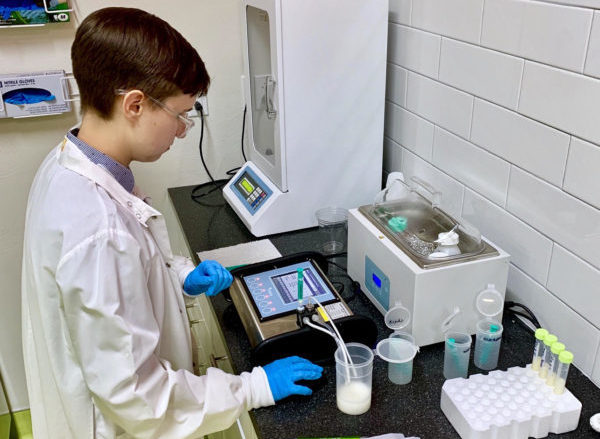

Two years in the making, the biobank recently came to fruition with grant support from the Henry L. Hillman Foundation. The lab collects milk samples, processes them to preserve essential components and stores them in a -80C degree freezer. The purpose of the biobank is to reduce barriers to studying human milk, which can inform research on everything from nutrition and immunology to oncology.

Dr. Hand’s research has shown that some bacteria may escape from binding to antibodies secreted by breast milk, contributing to a higher incidence of NEC. Dr. Hand and his colleagues use donor milk samples to demonstrate that while milk antibodies are produced homogeneously by a single mother over the course of an infant’s development, the antibodies vary widely between individual mothers. They hope to use their findings to match infants with the most protective donor milk for their specific needs.

“I think that the strongest benefit of the milk bank is that it allows researchers to capture a large number of samples and get a handle on just how diverse different milk samples are and what the sources of that diversity are,” says Dr. Hand. “Once we have identified a target breast milk component, the ability to easily understand whether it differs between mothers and is thus a potential contributor to a given disease is critical — and previously hard to do.”

Beyond NEC, donor milk can help babies with complex medical needs, including cardiac conditions, immune disorders, formula intolerance, renal diseases and failure to thrive. It can also serve as a bridge for healthy babies who require supplementation before discharge, boosting their mothers’ chances of breastfeeding success.

To better serve the outpatient population, the milk bank opened its first community donor milk dispensary at the Lehigh Valley Breastfeeding Center in Allentown. The dispensary model has allowed families in other parts of the country to quickly purchase small amounts of milk and starter supplies. The milk bank—which now partners with hospitals in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, New Jersey, and Maryland—is working to establish more dispensaries in the region.

Throughout its work, the milk bank prioritizes safety and medical ethics. Donor screeners—certified lactation consultants—follow the guidelines established by the Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA), which prohibits compensation of donors and outlines a rigorous screening process, including a detailed application and bloodwork.

“Viruses and bacteria that would not be a problem at all for term or healthy babies can be devastating for small preemies,” says O’Connor. “Despite the fact that milk banks serve some of the most fragile infants, there is little regulation.”

For example, HMBANA’s guidelines are not universally enforced. And although U.S. Food and Drug Administration food safety requirements provide guidance on handling breast milk, they don’t address the complexity of processing milk from multiple donors.

Frustrated by the lack of consistency in milk donation policies, the milk bank’s staff and supporters advocated for legislation to regulate and license milk banks in Pennsylvania.

Their work paid off in February when PA House Bill 1001, the Keystone Mothers’ Milk Bank Act, became law.

“The new law provides basic oversight for all organizations collecting or distributing human milk in the state,” says O’Connor. “We believe that such licensure will positively impact awareness and insurance coverage.”