New Brookings research explores the realities — and encouraging possibilities — of family-school engagement

In photo above, Butler Area School District parents discuss parent-school engagement at a Great Learning Conversations event, part of the Parents as Allies project, on Sept. 30, 2021.

When the pandemic forced schools to get creative about communicating with families, a surprising thing happened. As teachers worldwide committed to reaching families any way they could — texting, emailing, calling, video chatting and even knocking on people’s doors — they began really connecting with parents.

Schools were closed, and yet many teachers built stronger bonds with families than ever before. Some even connected with parents who’d been especially hard to reach. And parents reached back, jumping into the sometimes intimidating work of helping their kids learn.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Universal Education (CUE) had been digging into the subject of family-school engagement for more than a year before COVID-19 erupted.

The folks at CUE aim to help people understand and address inequality in education, and make strides toward the best possible education for all of the world’s kids. The pandemic has made teaching and learning difficult in ways no one saw coming, and it led these researchers to dive even deeper into the reasons why the family-school connection matters — and into understanding the roadblocks that keep it from happening.

“It’s a real moment to transform how we do family/school engagement long term,” says Rebecca Winthrop, CUE’s director. “Parents, moving forward, are really expecting to be more deeply engaged in their kids’ education.”

This week, Brookings has released data from surveys of more than 24,000 parents and 6,000 teachers in 14 communities across 10 countries. This included many communities in the Pittsburgh region.

The data is shared in the form of a “playbook” designed for use by decision-makers. But the insights — and the interactive database of tools and strategies they’ve built from this research — are also helpful for parents and educators.

The playbook, titled “Transforming Education Through Family-School Collaboration,” includes these insights:

FAMILY-SCHOOL ENGAGEMENT IS HUGELY VALUABLE — AND OFTEN IGNORED. Before the pandemic, communication between families and schools wasn’t a priority in most communities. There were no systems or habits in place to help these connections grow. Educators weren’t taught how to connect with parents. And many parents didn’t see a place for themselves in their kids’ school lives.

Yet Brookings has found that helping families and schools work better together is not just the right thing to do; it’s also the smart thing to do. Schools with strong family engagement are 10 times more likely to improve student learning outcomes.

After looking at 500 strategies used in communities around the world, Brookings found that increased parental engagement in learning can:

Improve the attendance and course completion of students.

Improve the learning and development of students.

Redefine the purpose of school for students.

Redefine the purpose of school for society.

Best of all, this progress isn’t expensive. The study found that it can actually “deliver the equivalent of three additional years of high-quality education for a low per-student cost.”

WE NEED TO HEAR EACH OTHER. Connecting is clearly important. But right now, some basic roadblocks exist in communities all over the planet.

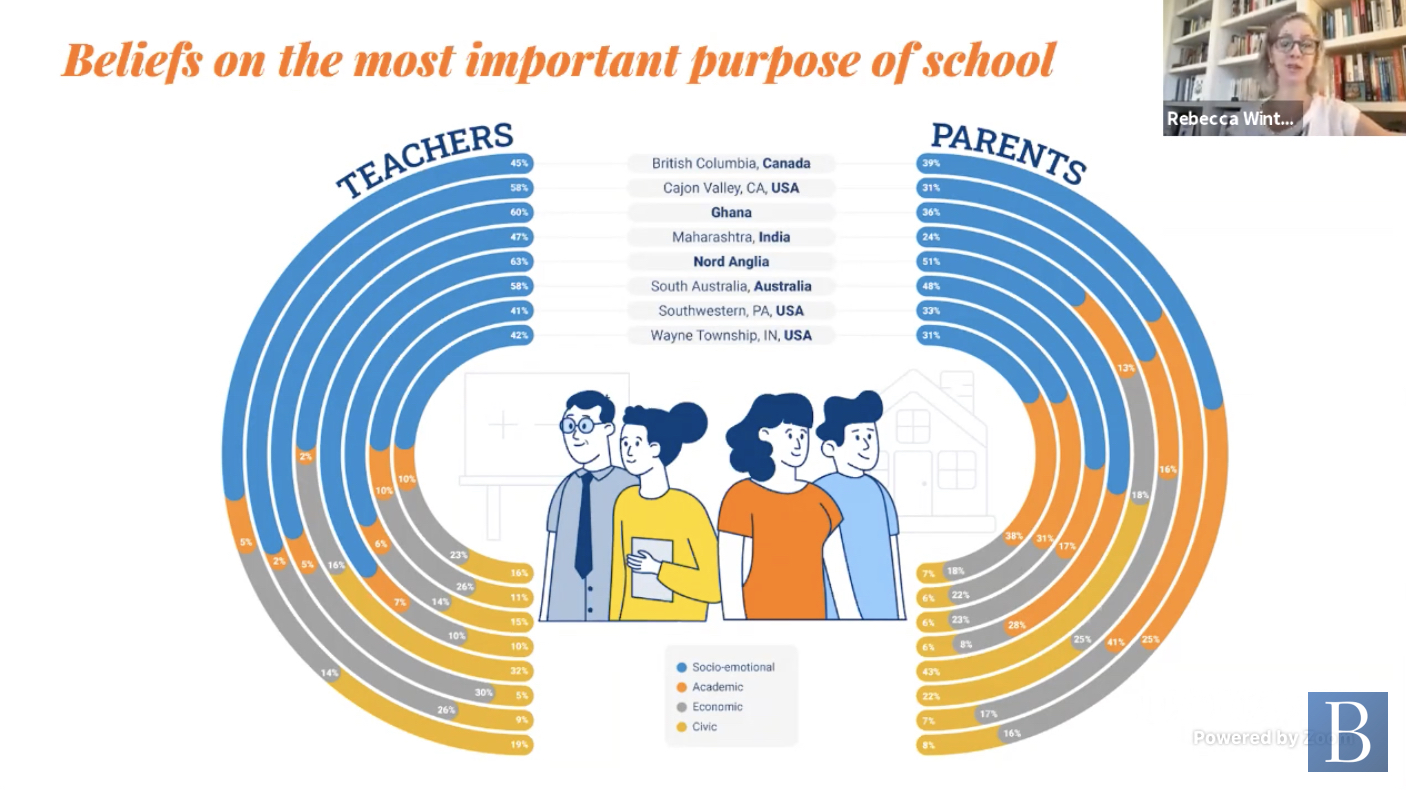

Parents and schools rarely talk to each other about their main goals for schooling: Is it purely a place for academics? Or a place to train for the best possible job, or learn about being a good citizen, or become a person with the social and emotional skills to get along with others and navigate the highs and lows that life throws at all of us?

Some parents and schools reflexively assume they disagree. Brookings found that throughout the world, many parents and schools see social/emotional learning as a key purpose of school. Yet each group said they believe the other group mainly cares about academics.

The data also found that a child’s age greatly influences parents’ beliefs and perceptions about what makes for a quality school experience. Most parents with younger children focused more on their child’s well-being, while parents of older students focused on academics.

Parents’ own levels of education also play a role in who shapes their beliefs about school. Parents with lower levels of education are more likely to be influenced by people in their everyday lives.

In different parts of the world, this might be the child’s teacher, a local religious leader or another community leader, or perhaps other parents in the community. More highly educated parents are more likely to listen to people outside of their local community, such as admissions officers at universities, journalists and experts quoted in the media.

Whatever parents and teachers may currently believe, one thing is clear: If both sides really listen to one another — discussing their views on the purpose and goals of schooling, and mutually respecting what they hear — common ground is possible. That sets the stage for working together to help children thrive.

WE CAN SEIZE THIS MOMENT. Our world is evolving rapidly—not only due to COVID but also because of globalization, automation, climate change and other external pressures. As that happens, schools and education systems must adapt. As the global COVID-19 pandemic made clear, real partnerships among families, communities, and schools can help us navigate this time of disruptive change.

With parents more involved than ever in their kids’ learning, this moment is an opportunity to build connections for the long term.

But Brookings found three major barriers to parental engagement around the world. First, schools aren’t designed to engage with parents. Second, teachers and school administrators aren’t usually trained in effective ways of interacting with parents. And third, power dynamics leave many parents uncomfortable and unsure of their place in the school community.

Noticing these roadblocks is the first step toward tackling them. The interactive tools included in the Brookings playbook can help with that process.

Parents will find strategies to better support their children’s learning and claim a voice in transforming education systems. Teachers and schools can use the playbook’s tools to better understand the perspectives of parents and develop new ways of collaborating. And ideally, policymakers will use this knowledge to transform education in their communities.

MORE RESEARCH TO COME

Brookings’ research and the resulting playbook is one part of the global Parents as Allies research project, funded by the Grable Foundation. This collaboration between four organizations – the CUE at Brookings, the Teachers Guild x School Retool team at the groundbreaking design firm IDEO, the Finland-based education innovation nonprofit HundrED, and Kidsburgh – will continue throughout 2021 as these organizations explore the many facets of parental engagement.

IDEO’s team recently completed a design sprint process with 14 communities around the world to devise impactful and affordable hacks to increase parental engagement. HundrED sought out innovative approaches happening worldwide and published details about 12 of these in their recent Parental Engagement Spotlight report.

And throughout this fall, Kidsburgh is hosting a series of in-person brainstorming sessions with parents and educators called the Great Learning Conversations. Kidsburgh will also be publishing a series of articles exploring the Brookings playbook in further depth in the coming weeks.