Phones and kids: new pediatric guidelines, expert advice and info on new school rules

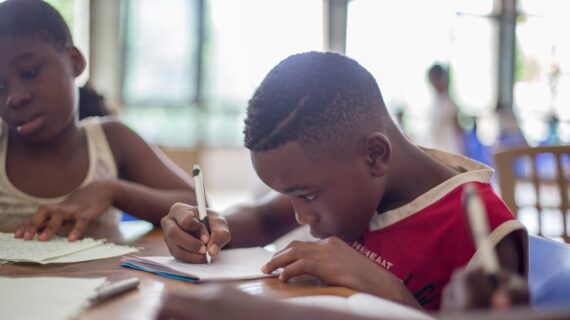

Photo above by Julia Coimbra via Unsplash.

The first iPhones and Androids hit the market when today’s high schoolers were babies. They’ve never known life without smartphones. And today, the Surgeon General’s office estimates that 95 percent of kids ages 13-17 and nearly 40 percent of kids ages 8-12 use social media, connect to the internet and use a massive array of interactive apps through their phones.

Until recently, the advice was to limit kids’ screen time to two hours per day or less. That wasn’t always easy — and we’re now discovering that it wasn’t enough to just focus on the number of minutes kids spent in the glow of their screens. It matters what they’re watching and reading, and how it affects a given child or teen.

Phones connect our kids with information and ideas, but they also appear to be causing increases in anxiety, depression, bullying and other distractions, especially in the classroom.

How do parents help their kids navigate our digitally connected world?

Last month the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health unveiled its “5 C’s of Media Use” – a guideline for parents to better understand media influences and to strive for healthy screen time habits (we break down all the details on that below). And schools have begun testing new rules and grappling with the growing issue of phones in schools at all grade levels.

We’ve got all that information, along with info on how “starter phones” can help:

SCHOOLS TAKE ACTION

To help control negative effects from cell phone overuse, schools are increasingly invoking strict rules to eliminate phones in classrooms. And earlier this month, PA state senator Ryan Aument (R–Lancaster) drafted a bill to lock up student phones due to the “steep decline in mental health in children since the early 2010s,” according to his website.

Data from Common Sense Media also found that 97 percent of students surveyed used a phone on average for 43 minutes during school hours, and 37 percent of that time was spent on social media.

Starting this year, Sto-Rox School District banned cell phones in classrooms in all grades.

Here’s how it works: Over the course of about 10 minutes, nearly 600 students in grades 7 through 12 enter their school building, hand their phones to a staff member who places it in an envelope with the child’s name on it, then it’s put in a bin to be locked in storage for the day. The students then pass through metal detectors and head to breakfast. Phones are returned by the students’ last period teachers during the day’s final five minutes.

The process was planned carefully and has been running smoothly. “We are very good at it,” says Sto-Rox superintendent Megan Marie Van Fossan. “We’re very strategic.”

And the impact? At the start of the school year, the students weren’t happy about the new policy. But then positive changes began surfacing.

Van Fossan says kids have begun talking to each other again in the cafeteria. Back when phones were allowed, the cafeteria was a relatively quiet place where students were focused on their phones rather than one another. Mornings in the hallway are now the same: Rather than scrolling on their phones or texting, students are greeting each other as the day begins.

Rather than revolving around social media, these students’ days are full of in-person interaction and connection. No parents have complained about the policy, Van Fossan says, and the rule isn’t difficult to enforce.

Other school districts in the region have been taking notice.

“We get phone calls and emails (from other school districts), saying, ‘We are looking at going to this policy. Tell us about your experience,’” Van Fossan says.

Why ban phones?

Phones were taken out of seventh and eighth grade classrooms last year and were never permitted in kindergarten. But the choice to start a district wide ban came because of increasing safety and security concerns.

“Kids were texting one another to meet, fight someone in the bathroom, hurt someone after school,” Van Fossan says. “We don’t need that going on during the school day.”

Students were also paying less attention in class.

Beyond helping with focus, the new system also helps inspire kids to be on time: Late students must drop off – and retrieve – their phones at the school’s office, potentially adding 20 minutes to the end of their school day.

In the Pittsburgh Public Schools’ 54 buildings, the electronic device policy “generally prohibits students from using, displaying or turning on cell phones on school grounds.” And in some PPS high school buildings, student phones are sealed in pouches at the start of the day.

But in many buildings, students have traditionally kept their phones with them.

“A lot of our high schools are leaning (toward) collecting phones; not every high school does,” says Carrie Woodard, director of school counseling for the district.

In recent years, PPS counselors have seen increases in cyber bullying in addition to anxiety and depression symptoms in students who arrive at school upset from social media postings made after school hours.

“It’s something I think we’ve been battling for over a decade now,” Woodard says.

What can help besides banning?

To help win that battle, Woodard said it’s important for educators and school counselors to support the whole child, academically and personally by:

- Being aware of the potential negative effects of social media and cell phone use, and promoting a balance of use with students.

- Doing one-on-one counseling or, when appropriate, group counseling for students who are experiencing the same issues. The group can meet and discuss healthy solutions.

- Teaching healthy boundaries, like self-advocacy skills (how to stand up for yourself, how to deal with social media comparison to unrealistic standards that affect self-esteem and how to deal with cyberbullying) and finding trusted adults they can confide in.

Some parents, Woodard says, are anxious about phones being taken away from students. They want to have instant communication with their child in the event of an emergency.

“From the school level, we can always assure them,” she says, “that if there is an emergency there are systems in place where the educational team will get in touch with the parent.”

What is a starter phone?

Starter phones are entry-level devices that allow kids to text, call and store photos. Some have limited access to the Internet or social media. They come in many shapes and sizes, and are usually budget-friendly. Here are some options parents may want to pursue:

The Bark Android phone has parental controls included. It sends alerts about your child’s texts and searches and has location tracking. Approval to download apps is necessary. You can also install a Bark parental control app on any smartphone. Plans starting at $39/month at Bark.us

Also an Android phone, the Pinwheel has parental controls built in, and there is no web browser so it has no direct access to social media. There are several models. Note that you won’t receive alerts about messages that will be a potential problem. The Plus 3 is $489 on Amazon.

The iPhone SE lets parents manage how much screen time a child spends in their browser. Through Apple’s Family Sharing, parents set screen time permission, approve what their child buys or downloads, and can disable apps and set limits from their own device. Like almost any iPhone, it can be set up with Apple’s parental controls. Costs starts at $429 from Apple.

The TCL Flip 2 flip phone allows calling and messaging, and it includes simple games and a limited web browser. $100 from Amazon.

The Nokia 2780 Flip phone is easy to use for texting and calling. $90 at Best Buy.

The Gabb Phone has no internet or social media and no app store. It does include a GPS tracker, and other basics like a camera, calculator, photo album. $75 at Gabb.com.

SCREEN TIME ADVICE FOR EVERYONE

Last month the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health unveiled its “5 C’s of Media Use” – a guideline for parents to better understand media influences and to strive for healthy screen time habits.

The AAP is looking for a way to help parents and educators understand the issues cropping up with phones and other screens, and understand how they can help the children in their lives, says Pamela Schoemer, MD of UPMC Children’s Community Pediatrics. Schoemer tells Kidsburgh she has discussions about screen time effects in about half of her patient visits.

The 5 C’s stand for:

- Child (how they are affected by social media and its potential drama, social anxiety and age-inappropriate content)

- Content (how media use influences positive or negative relationships through things like violent video games or unrealistic beauty standards)

- ways to Calm down (managing strong emotions and addressing things like having trouble falling asleep)

- Crowding out (reducing media usage and replacing it with more family quality time and learning to combat social media’s many “hooks” that keep people scrolling)

- Communication (talking as a family about social media and asking questions)

The “calm” element of the guideline, Dr. Schoemer notes, typically comes up when there are issues with falling asleep – something that can spill over into the ability to focus or even stay awake throughout the next school day.

“Kids need the ability to calm themselves and to deal with their emotions,” she said. “So often I see parents, especially with younger kids…putting something (a cell phone or tablet) in front of their child to calm them.”

Instead of handing kids a digital device, she suggests:

- Explaining that it’s okay to be angry, giving “voice” to a child’s emotions, allowing time and space to process their emotions and giving them control in another way. For example, at bedtime, telling them it’s time to put their tablet or phone away and then asking them to select which pajamas they want to wear.

- If they are physically acting out, allowing them to do something active that isn’t violent, like hitting a balloon.

- For teens, who may be engaged in an online conversation or some other type of interaction, parents can try making kids aware of their presence and let them know it’s time to move to another activity (like homework or bedtime).

Dr. Schoemer considers that final “C,” communication, to be the best resource for parents. It’s helpful to have discussions about time limits with devices. But communication isn’t just about how many minutes a child is looking at a screen. It’s also important to know what your child is looking at it and explore its impact.

It’s okay to ask what your child is looking at, she says, and it might even lead to a moment of shared laughter: “A TikTok can be just as funny to us as it is to them.”

Valuable screen time, like exploring interests, communication with extended family or for schoolwork, is great. Healthy screen habits at home can include educational videos that help deal with emotions or those that encourage an activity, like cooking or science experiments for younger children. Anything on PBS Kids (from “Mister Rogers’s Neighborhood” and “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood” to the friendship-focused show “City Island“) is suitable for younger children over the age of 2 or 3.

“All screen time isn’t equal, and you have to assess it,” Schoemer says. “If that young person is following an influencer or playing video games with more violence or rudeness or language that you don’t approve of or, unfortunately, is being bullied, those are bad screen times.”

One last note: Kids are smart and may manage to work around parental controls. So parents should check devices, and also educate themselves by consulting friends, pediatricians and other resources like the AAP website or Common Sense Media.