Pittsburgh school districts are finding innovative ways to support kids during coronavirus closings

Dr. Jill Jacoby isn’t a fortune teller. But the week before Gov. Tom Wolf declared a state of emergency in Pennsylvania, closing schools due to the coronavirus outbreak, the superintendent of Fort Cherry School District sensed that something was happening beyond anything she’d experienced as an educator.

“As soon I saw this thing coming, I said, ‘we have to get moving,’” Jacoby says. “That week prior, our faculty got 10 days’ worth of curriculum taken care of and organized.” By March 13, when school closings were announced, she says, “we were ready to go.”

The coronavirus outbreak has disrupted school districts throughout the Pittsburgh area. Administrators and teachers have been forced to rely on remote learning or lesson packets delivered to homes. They’ve had to make sure students without devices and internet access can continue classes. And for students who rely on meals provided by schools, administrators devised ways to keep them fed.

Some school districts, such as Brentwood, “started at ground zero,” says superintendent Dr. Amy Burch. Administrators and teachers quickly created curricula in response to schools closing. Other districts, including Elizabeth Forward, had the infrastructure in place to transition to remote learning, according to superintendent Dr. Todd Keruskin.

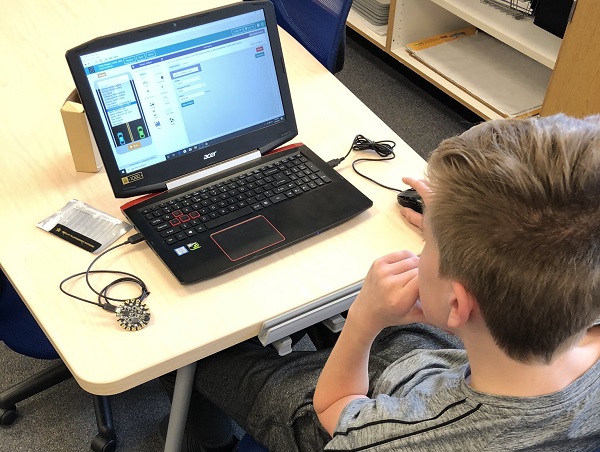

“We’ve been trying to transform our classrooms from traditional classrooms to modern classrooms,” he says, noting that for the last eight years all students in the district have been 1-to-1, one device per student, each receiving an iPad for use during school hours, at home and over breaks.

“But it’s not all about the technology. It’s about the professional development and how teachers are teaching using this technology,” Keruskin says. “For the last two or three years, we’ve been working to make sure each teacher feels comfortable using that new blended learning model.”

Remote learning isn’t a new phenomenon. But for traditional brick-and-mortar schools, the reliance solely on online or remote learning is new.

By April 9, any hope for a return to conventional classrooms ended when Gov. Wolf announced that all schools in Pennsylvania are closed for the rest of the academic year. The burden is one that is shared by teachers, administrators, parents – and 1.7 million students.

One thing that helps facilitate remote lessons is the current generation’s familiarity with tablets, laptops, cell phones and other devices.

“They are digital natives,” says Bart Rocco, a former superintendent for the Elizabeth Forward School District and a Grable Foundation fellow. “The kids know the technology sometimes better than the teachers, and the gap that exists is that we have to make sure the professional staffs engaging kids in learning are up to speed with the technology and have the wherewithal to push that out.”

A shout out to AIU

Comfort with technology doesn’t automatically mean kids are going to learn, however. Familiarity with technology is good, but not necessarily conducive to learning, says Rosanne Javorsky, the interim executive director of the Allegheny Intermediate Unit.

“Kids are more tech-savvy today, but they’re not necessarily using technology to engage in learning opportunities,” Javorsky says. “Not everyone necessarily enjoys the online learning experience, and that’s from the youngest students to university students I’ve talked to who are longing for face-to-face classes.”

Since schools started closing in mid-March, the AIU, a regional public education agency that provides specialized services to administrators and educators and is a liaison with the Pennsylvania Dept. of Education, has ramped up its interactions with school districts.

Since mid-March, well over 2,000 teachers have participated in professional development programs offered by the agency, including how to teach via Zoom, accessibility tools, creating virtual assessments, and facilitating learning via video conferences.

“We’re doing a lot about how to teach online, how to teach kids online, what’s different about teaching online, and helping them understand the tools that they have available,” Javorsky says.

Critical lifelines to families

While maintaining the quality of education is essential, so is making sure students get meals. State and local agencies have provided vital lifelines, says Dr. Bille Rondinelli, formerly the superintendent for the South Fayette School District and a Grable Foundation fellow.

“The superintendents we’ve spoken with, their main focus initially in the first couple of weeks was getting food to the children and making sure they have the necessities they need,” Rondinelli says. “Now that they have that, then they’ll move to the technology.”

School District snapshots

Here are snapshots of a few local school districts and some of the initiatives they are taking during coronavirus outbreak.

Brentwood School District

Student population: 1,200

Brentwood Borough is a mere 1.5 square miles. The compactness of the borough served administrators well when schools were ordered to close on March 13, according to superintendent Dr. Amy Birch.

“We were able to get a food program up and running by the 17th,” Birch says, noting that meals are being served to students who qualify for meal assistance programs Mondays through Saturdays.

Teachers worked quickly to create online lessons. But only 68 percent of families in Brentwood had reliable devices, and 20 families had no reliable internet service. As a remedy, the school district has passed out 170 laptops to families and provided wi-fi hot spots to those without internet service.

“The other thing we are asking teachers to do is make personal phone calls to homes,” Birch says, “just to check on kids.” If families can’t be reached, school officials make follow-up phone calls.

“What we’ve learned is how much stress our families are under,” Birch says. “It’s definitely taken priority over education. … In a household environment where the stress level is off the charts, it’s not reasonable to expect them to complete academics on top of that. We’ve tried to make this as flexible as possible for our youngest learners, especially.”

Elizabeth Forward School District

Student population: 2,330

The Elizabeth Forward School District was fortunate to have 1-to-1 learning in place when the coronavirus outbreak shuttered Pennsylvania schools in mid-March. For families without internet connections at home, it was relatively easy to supply hot spots.

Students have been adapting as well as can be expected, according to superintendent Dr. Todd Keruskin. “It hasn’t been this huge jump for kids,” he says.

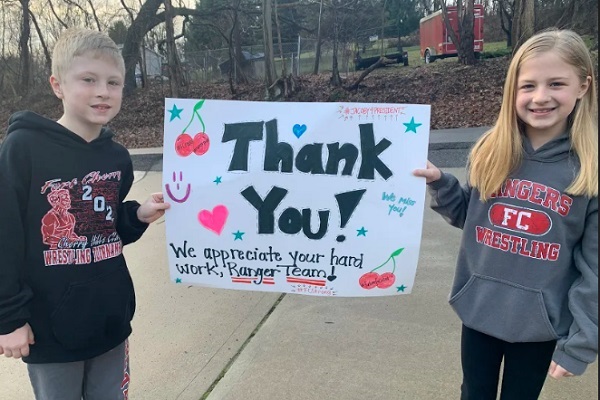

Replicating the social aspect of attending school – the camaraderie, the interactions between students and teachers – has been a bit more challenging. Virtual spirit and crazy sock days, wearing athletic game jerseys or the school’s red-and-black colors have been used to maintain school spirit.

“Social media lends itself a little bit to that social interaction,” Keruskin says.

Fort Cherry School District

Student population: 974

The district has been using online blended classes for grades 7-12 for the last few weeks. As of April 15, online instruction availability extends to grades 5 and 6. For K-4 students, the district is relying on snow day packets, with 10 days of instruction developed by teachers broken down into daily lesson plans.

“For my families that don’t have personal technology or reliable wi-fi, we’re making personal contact,” says Dr. Jill Jacoby, Fort Cherry’s superintendent. “The teachers are calling and touching base. Education is an important part of it, but the human aspect of it is, too. We want to make sure our families are OK. We have a high poverty level here, and in the past 10-15 years, we went from 20 percent of families receiving free or reduced lunch to 43.7 percent.”

Shaler Area School District

Student population: 4,200

Last summer, Shaler Area School District applied for and received permission to be part of the Flexible Instruction Day (FID) Program administered through Pennsylvania’s Department of Education. FID allows school districts to meet the 180 days of instruction required by the state through online or offline instruction, or a combination of the two and is limited to five days total.

Just as the seriousness of the coronavirus outbreak became apparent, Superintendent Sean Aiken and his staff started preparing work for students. “At the very least,” he says, “we could buy ourselves five days we could use in case of this emergency,” he says. “Beyond that, we would move forward with a remote learning plan.”

When schools closed on March 13, classes in the district were suspended for five days, so Shaler administrators could prepare an exhaustive plan to continue educating and feeding students. With at least 38 percent of students qualifying for a meal assistance program, getting food to designated pickup points has been a point of emphasis.

“I’d say in Allegheny County as a whole, there were probably only seven districts that jumped into remote learning right away,” Aiken says. “We said, ‘we’re going to let the dust settle and feed kids lunch and breakfast.’ Our focus was their immediate needs and meeting the needs of the community.”