Pittsburgh Teen Brain Report: Kids can make better decisions than we expect

The mere mention of the word “adolescence” can strike fear in adults. It’s long been synonymous with the most volatile, confusing time in a kid’s development — a time characterized by heightened emotion, poor decision making, social anxiety and turbulent hormones.

Parents, remembering their own teenage years all too well, understandably hesitate to let their teens out the door.

But what if science suggests a different approach? What if — as Dr. Beatriz Luna of the University of Pittsburgh says — “Adolescence is not a disease,” but a crucial time of exploration and creativity?

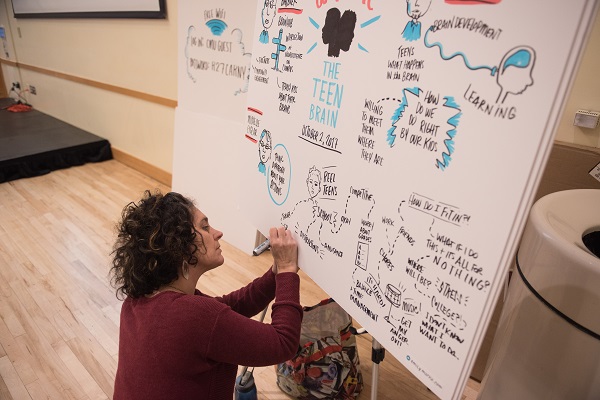

That was the premise of “The Teen Brain,” a daylong symposium hosted by Carnegie Mellon University’s BrainHub. Gerry Balbier, BrainHub’s executive director, billed the event as an opportunity to help youth-serving organizations better serve kids by sharing the latest in teen brain research.

“We work at the intersection of biology, psychology, computer science, statistics and engineering to advance discoveries in brain science,” says Balbier. “And with this conference, we’re working to get our ideas out the front door.”

Those ideas fall into three broad groups: decision-making, creativity, and mindfulness. Knowing how teens experience each can help service providers, policymakers and parents “work with the brain instead of against it,” says Grant Oliphant, president and CEO of The Heinz Endowments, which sponsored the symposium. “We’re sending a signal to young people that we’re willing to meet them where they are.”

But adults often have wildly wrong ideas of where those young people are. As an introductory video created by students from Steeltown Entertainment Project illustrates, contrary to popular assumptions, adolescents aren’t necessarily consumed with clothes, parties and fitting in. Instead, they worry about getting into college. They worry about what to do with their lives. They worry, as one student puts it in the video, about whether they’re working hard for nothing. Teen’s concerns, in other words, are complicated — and more adult-like than we tend to think.

That’s because their brains are adult-like, too. “By adolescence, everything is there,” says Dr. Luna of the brain. “It’s really a time of fine-tuning.” Under ideal circumstances, teens can make rational, well-thought-out decisions about as well as adults can. But they’re also far more susceptible to sensation-seeking and rewards, which drives them to take big risks and sometimes make the types of bad decisions that we typically associate with teenagers.

Learning to balance risk and reward is a critical stage of life, says Dr. Luna. If anything, adults don’t give adolescents enough credit: It’s a time of peak physical health and creativity, and by taking risks, teens are finding their place in an ever-shifting world.

This emerging understanding of adolescence has profound implications for parenting, juvenile justice, and delivery of human services, according to conference organizers. Above all, those who work with teens would do well to listen to them, to try and understand them through the lens of brain science, and to help them develop plans for how to react when their emotions get the best of them.