Post-pandemic chronic absenteeism plagues the Pittsburgh Public Schools

This article by Mary Niederberger was originally published by the Pittsburgh Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, a media partner of Kidsburgh, which provides coverage of the issues that directly affect our local communities and the people who live, work and go to school in them. Photo above by Mary Niederberger.

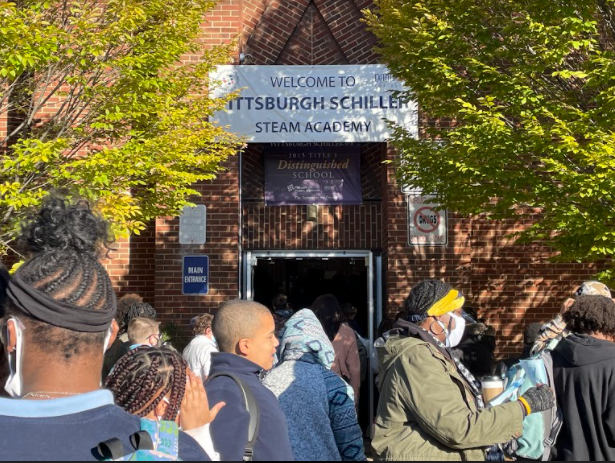

As Taylor Rosser, 13, joined her masked classmates in the morning sunshine outside of Pittsburgh Schiller 6-8 on Friday, she spoke of how happy she is to be back to in-person classes this fall after more than a year of mostly virtual learning.

“Being back in person, it actually feels good, except for the mask. I get to see everyone’s faces, kind of,” said Taylor, who is in eighth grade.

She’s also enjoying the face-to-face interaction with her teachers far more than the virtual interaction that took place during the 2020-21 school year. “Online, I kind of felt like I wanted to fall asleep because I was so tired after all of the periods,” she said.

Taylor’s classmates seem to agree with her as Schiller is among just a handful of schools in the Pittsburgh Public Schools (PPS) with healthy post-pandemic attendance and chronic absentee rates far below the district’s most recent average of 35%– a rate that has grown by about 10 percentage points since 2019-20.

Schiller’s overall attendance rate as of Friday was 94%, the fifth highest in the district. Its chronic absentee rate was 19%, a number that, while among the better rates in the district, frustrates school leaders who have worked diligently for the past several years to lower chronic absenteeism to single-digit percentages.

The district publicly posts attendance and chronic absence rates for each school on its data dashboard. The numbers are updated frequently and may vary slightly from those in this story.

The schools showing some of the worst attendance problems are Westinghouse Academy 6-12, with a chronic absentee rate of nearly 60%, and Milliones 6-12 where chronic absenteeism hovers around 55%.

A student who is chronically absent misses 10% or more of the school year. By the end of a 180-day school year, it amounts to 18 or more days. Chronic absenteeism is measured day by day and week by week at PPS, said Rodney Necciai, assistant superintendent of student support services.

It’s been a significant problem with numbers rising during virtual learning last school year and continuing into this fall when school buildings reopened.

Getting students back in the building on a regular basis this fall “is definitely a challenge,” said Necciai, “It continues to be a challenge.”

PPS Interim Superintendent Wayne Walters addressed the district’s chronic absenteeism as a participant in the A+Schools report to the community this morning. He thanked A+ Executive Director James Fogarty for bringing the issue to light in the report.

“All of our efforts to improve teaching and learning rely on students making it to school everyday,” Walters said. “Recent data received by our board of directors emphasized the need to pay attention to chronic absenteeism and the number of days that students are not in school as each day is critical for optimal learning.”

Walters said that solving the problem of chronic attendance “will require a deep collaboration with all stakeholders.”

Necciai said district officials are aware of the importance of getting students back into the classroom: Students who aren’t in school can’t learn and students everywhere have learning gaps resulting from interruptions and changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pittsburgh is not alone. Chronic absenteeism increased across the nation during virtual learning in the 2020-21 school year and continues this fall as students return to buildings. Some states reporting high absentee rates include Ohio, California, Massachusetts and New York.

The healthy attendance at Schiller is a bright spot. Across the district, more than 30 of the 54 schools had chronic attendance rates above 30% as of Friday.

The only schools with higher chronic absence rates than Westinghouse and Milliones were the alternative schools Clayton Academy, 63%, and the Student Achievement Center, 74%, and Oliver Citywide Academy, which provides special education services, 66%.

The numbers are not much better at most of the city’s 9-12 high schools with chronic absentee rates just under 50% at Perry, Carrick and Brashear.

In the lower grades, Faison K-5 has the highest chronic absenteeism at 55% followed by Arlington PreK-8 at 49%.

Four other elementary schools, King PreK-8, Langley PreK-8, Grandview K-5, and Weil PreK-5, had chronic attendance rates above 40%.

Overall attendance at each of those schools is also low, ranging from 64% at Clayton to 82% at Brashear. Overall attendance in the district is about 88%.

The schools with low attendance and high chronic absentee rates tend to be those with high percentages of Black and/or economically disadvantaged students — two groups that national reports have identified as being hard hit by the pandemic’s interruption of traditional school. Those hits come on top of large achievement gaps that already existed in Pittsburgh and nationally between those groups and their grade-level peers.

Schiller breaks that mold, maintaining high attendance despite student demographics that show 67% are economically disadvantaged and 46% Black.

In Pittsburgh the chronic absentee rates broken down by demographic show about 41% for Black students, 34% for Hispanic students and 27% for white students.

Other groups with high percentages of chronic absenteeism include students with individualized education programs at 45% and students who are economically disadvantaged at 43%.

A presentation at a PPS school board meeting in September by researchers from the Regional Education Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Education showed a direct link between chronic absenteeism and course failures in the Pittsburgh schools.

The researchers analyzed performance data provided by PPS and found: “The percent of students who failed a course increased by 22 percentage points for those who were chronically absent in first semester 2020-21, compared to those who were chronically absent in first semester 2019-20.”

Course failures increased by just 4% during the same time period among students who were not chronically absent.

Factors affecting chronic absences in Pittsburgh include transportation issues such as late buses that are still being worked out and students’ difficulty in getting back into the routine of being in a classroom all day, everyday Necciai said.

“Things like kids being able to grab something to eat or go to the restroom in their homes. There are different routines with back-to-the-building,” Necciai said.

Students who made transitions from elementary to middle school or middle school to high school during virtual learning may not feel comfortable in their new buildings, Necciai said.

“There are kids in eighth grade this year who didn’t get a full sixth grade and no seventh grade in school and we are asking them to be leaders in their school. Or kids who didn’t get a full ninth grade and 10th grade in school and now are in 11th grade which is a pivotal time,” Necciai said.

Necciai said he’s uncertain how much the COVID-19 virus, and fear of it, may be affecting absenteeism.

He outlined some of the measures the district is taking to encourage students to attend school regularly and to help remove obstacles that may be preventing that.

“We are knocking on doors” of students who are chronically absent, Necciai said, as well as partnering with the attendance improvement program Focus on Attendance and identifying other community partners at each school who can help school staff connect with families.

Necciai also urges parents who are facing obstacles in getting their children to school to reach out to school counselors or social workers. “We need to hear from families,” he said.

Schools are also using student assistance teams to explore the issues students are experiencing that are preventing them from attending school.

Necciai said Schiller can serve as a model for other schools in the district given its success in connecting with students and their families and getting them to prioritize attendance before and throughout the pandemic.

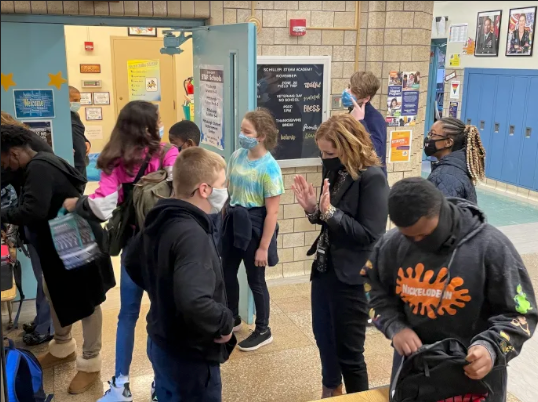

Schiller Principal Paula Heinzman and counselor Lana Shaftic have created a system of accountability, incentives and rewards for students that is used by the entire school staff. The system was created pre-pandemic and has continued throughout.

Students with chronic absences are assigned a “Be There Buddy” from among the adult school staff. That buddy checks in daily with those students, encouraging regular attendance and providing incentive and rewards. Rewards can range from small items such as an item from the school store to permission to attend a field trip.

The effort was started after the 2012-13 school year when Schiller was identified as a school with a high chronic absentee rate. At the time the rate was 36%. Through the efforts of school staff, it fell to 5% in February 2020, a month before the pandemic shut down schools.

Of counselor Shaftic, Heinzman said: “She is the best when it comes to attendance. She’s relentless in getting our attendance to where it needs to be. You just need a champion to do that. She has those relationships with the parents and it’s not always positive. She has to have these tough conversations.”

Shaftic moved her patrol of absences online during virtual learning, popping into classes all day long and nudging along students who were not in virtual class. Heinzman maintained a virtual treasure chest that students could visit during online learning to choose their rewards.

The school staff also kept up its systems of rewards, mailing trinkets to students who reached certain academic and behavioral milestones.

Taylor said she enjoyed receiving rewards in the mail during virtual learning. Though the online classes tired her, she stayed so engaged with online learning that she showed significant progress in the interim math assessments Schiller students took this fall.

“I just thought harder, read over the questions multiple times. I feel like the teachers they’ve helped me grow and make sure I understand what I’m reading before I answer the question,” Taylor said.

Heinzman and Shaftic are bothered by their current chronic absentee rate and want to work to get it as close to zero as possible.

“That really should be the norm. It should be because our kids are worth it,” Heinzman said. “We just can’t throw up our hands and say ‘Everybody is experiencing it.’ We are not going to be status quo, we are not going to feed into that.”