PPS and other districts find obstacles as they address pandemic learning interruptions and gaps

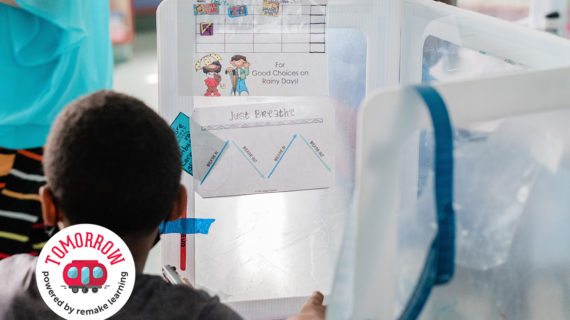

Photo above taken on PPS students’ first day back at school after holiday break by Mary Niederberger, courtesy of PINJ.

Weeks before classes started in the Pittsburgh Public Schools last fall, school leaders embarked on intensive planning for the students’ in-person return in the midst of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic

Students had been out of the buildings, for the most part, since March 2020.

They planned meticulous safety protocols to prevent virus spread and anticipated the need for extra patience and counseling with students who had been away from classroom routines for more than a year.

They also set the stage for one of the biggest challenges they would face: Determining the extent of academic deficits – educators call it learning loss or unfinished learning – created during months of remote instruction and moving quickly to address them.

National and local assessments already showed students were months behind in reading and math, with vulnerable students – including minority and poor students and English language learners – even further behind creating larger educational inequities than existed before the pandemic.

PPS school leaders knew things wouldn’t be the same as when students left the classrooms in March 2020, but they worked with the belief that once students were back in person, plans to address academic and social/emotional issues could be put into action.

“Everybody thought things would be fine once everybody got back,” said PPS Interim Superintendent Wayne Walters in an interview. “It wasn’t like that. The pandemic really threw us for a loop.”

Walters said he and his staff now understand that “the unfinished learning is multi-faceted and it’s not just instructionally-based.”

Throughout the first months of school, chronic absenteeism – currently about 42% districtwide – kept students from attending regularly. Transportation problems caused by a bus driver shortage made some students late for school daily. Discipline issues were frequent in some schools and sometimes got physical. Social media threats against schools raised fears, keeping some students away, and counselors and social workers were overwhelmed with the social and emotional needs students brought to school after their time in isolation.

Last week, a new complication emerged as students returned from holiday break: Staffing shortages that called for more than two dozen Pittsburgh schools to revert to online learning for days at a time. District press releases attributed the staff call-offs to “positive cases of COVID-19, COVID-related quarantines, and other staff-related absences.”

The school closures are the result of a shortage of substitutes available for teachers, bus drivers, cafeteria workers and other staff needed to keep buildings open.

“We’re really a football team without a bench,” Walters said in an interview before the holiday break as he anticipated the coming problems.