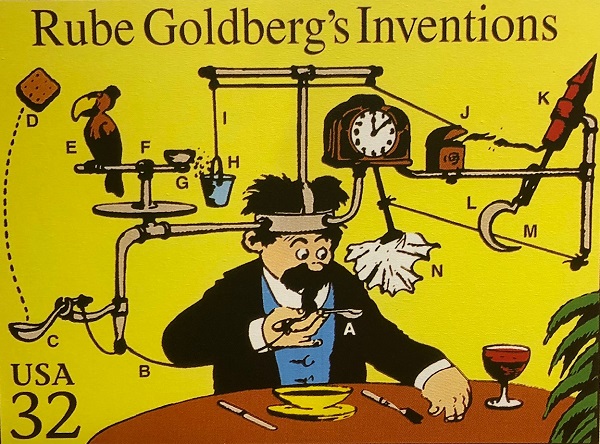

Rube Goldberg’s zany chain-reaction machines come to life in new exhibit at the Children’s Museum

This story was first published on Oct. 16.

Rube Goldberg wanted to be a cartoonist. His father thought that was a foolish pursuit and sent him to the University of California, Berkeley, to become an engineer.

His first job after graduating in 1904? Working on San Francisco’s sewer system.

Not the best training for a young man who loved to draw. But if not for that job, Goldberg might not have won a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1948.

“Working in a San Francisco sewer must have been as pleasant as it sounds,” says Jennifer George, Goldberg’s granddaughter and legacy director of the Heirs of Rube Goldberg Organization. “He just slogged through that for six months before he asked his dad if he could leave. Max (Rube’s father) agreed, and I think that spurred Rube’s ambition. I think he wanted to prove to his father that an artist could make a living and could matter in this crazy world of ours.”

With the world premiere of “Rube Goldberg: The World of Hilarious Invention!” opening at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, he will be introduced to another generation of fans. Here, Goldberg’s inimitable drawings of zany inventions are reimagined by artists, fabricators, and other creative types as life-sized interactive pieces.

“When we began doing design and brainstorming sessions, what was so exciting to me was how the creative team really helped me look at my grandfather’s work in a different way,” George says.

“I’m still in awe of what they have created for this show,” she says.

“With what we do at the Children’s Museum and our commitment to play with real things, it was the perfect match,” agrees Anne Fullenkamp, director of design, of the partnership with Heirs of Rube Goldberg Organization.

Kids – and grownups – will be fascinated and entertained at the recreations of some of Goldberg’s silly cartoons, each of which give specific directions.

Pull the rope on “A Simple Way to Sharpen a Pencil” to open a window to fly a kite. The kite string opens the door to a moth hive and moths escape to eat holes in a flannel shirt. The shirt rises, lowering a boot that kicks the switch to an electric iron. The iron burns the pants on the ironing board, sending smoke into a hole in a tree, disturbing a guinea pig who leaps from the tree into a basket. The basket lowers on a rope that raises a birdcage, where a woodpecker begins tapping on a pencil you hold and turn to get a good point.

No one can watch it once and walk away without laughing and pulling the rope a few more times to set it all in motion again. The action is mesmerizing.

Rube Goldberg was the inspiration for artist Ed Steckley’s “An Epic Way to Paint a Picture” in another display. The end result of the series of machinations is rotating lawnmower blades that turn paint rollers onto a “painted” light screen.

Kids can reset the Goldberg machines that set balls rolling, hammers dropping, and goofy noises singing out. A magnetic wall allows kids to engineer their own crazy chain reaction contraptions with a variety of tubes and chutes. Smaller kids can build at an activity table. All can practice their cartooning skills in the exhibit’s Art Studio, then give their masterpieces a whirl on the Revolvometer.

Goldberg started to draw cartoons in what was considered the form’s Platinum Age from 1897 through 1938. It was during this era that publishers realized they sold more newspapers when images were featured. Few cartoonists were more prolific than Goldberg, who started working for the San Francisco Chronicle. When he joined the New York Evening Mail, he earned the staggering annual salary of $50,000 in 1915, more than $1.2 million in today’s dollars.

He drew approximately 50,000 cartoons during his career, but only about 12,500 originals exist – 12,000 in the Bancroft Library at Cal-Berkeley, and the others owned by his descendants.

The rest of the cartoons were discarded.

“Once they were printed, they would throw away the originals,” George says.

The sum of 50,000 cartoons seems incredibly high, given that Goldberg started publishing cartoons in 1904 and would continue to do so until his death in 1970. That’s an average of more than 750 cartoons per year.

“It’s overwhelming,” George says. “He was really a workaholic. My grandmother, his wife, said he never took vacations. He just didn’t like them. He preferred to go to work. He knew there was an empty spot in the newspaper every day for him, and he had to fill it.”

Despite the fact that Goldberg hasn’t been alive for almost 50 years, his work is still relevant. There are YouTube videos touting Goldberg-like inventions (his is the only given name recognized by Merriam-Webster as an adjective). The engineering principles applied in his drawings are instructive for STEM and STEAM learning.

Goldberg-inspired movie scenes in “Back to the Future,” “Goonies” and Wallace and Gromit’s ”Curse of the Were-Rabbit” delight viewers with their over-engineered contraptions.

With this new exhibit, which will travel across the country when it closes here in May, we suspect Rube Goldberg’s influence will continue to charm and motivate enthusiasts for another hundred years to come.