Space is the next frontier for Pittsburgh kids with sky-high ambitions

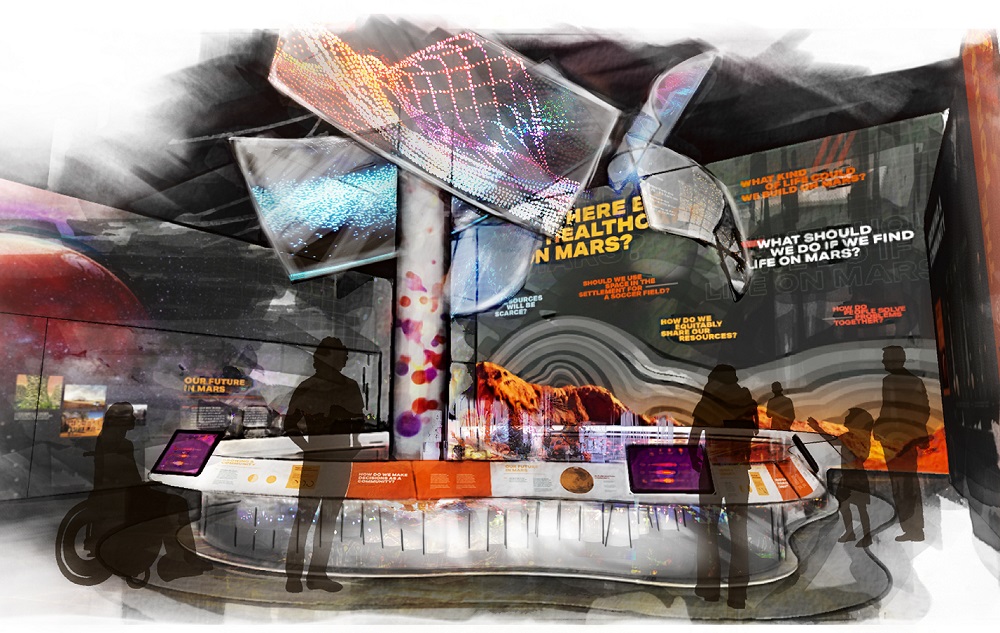

Photo: Rendering of the Our Destiny in Space exhibition courtesy of Carnegie Science Center.

This article first appeared in NEXTpittsburgh, a media partner that focuses on the people advancing the Pittsburgh region.

Pittsburgh is prepared to face a future dominated by the emerging technologies of robotics, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and medicine.

But what if we stood back a little bit … and looked up into the night sky?

The dream of space exploration has new momentum now — not seen since the so-called Space Race of the 1950s and 1960s. And a new partnership is positioning Pittsburgh to play a major role in that future.

On June 9, the Carnegie Science Center announced a new partnership designed to inspire and build a pipeline of talent for a new “space economy” in Pittsburgh. It begins with a new exhibition gallery, “Our Destiny in Space,” and ends with companies like Astrobotic, which was just awarded $200 million to deliver a rover to the moon for NASA, controlled from its headquarters two blocks away from the Science Center.

“This initiative will create opportunities for our region’s children to one day find their place in the space industry,” said Jason Brown, director of the Carnegie Science Center, at the kickoff event. “This will give students opportunities to learn alongside professionals that are building it, right now, today, here in Pittsburgh.”

The project includes a new 7,000-square-foot gallery at the Science Center. The new permanent exhibit, Our Destiny in Space, moves away from the familiar, introductory “science 101” content, noted Brown. After consulting with educators and students from Pittsburgh Public Schools, the Science Center created an immersive exhibition introducing students to “questions about our shared humanity, and how they are addressed as we venture ever deeper into space.”

It’s expected to open in the fall of 2022, with a focus on Mars exploration — particularly the path from Earth to the Moon, and then on to Mars.

“The big idea for Our Destiny in Space is that the questions we’ll face in the future for humans living on Mars are the same as those we face here on Earth today,” said Brown. “As we imagine a better future on a different planet, we discover what’s needed to make that future on Earth a reality as well.”

“The goal of this initiative is to make space accessible to all, but especially to marginalized groups and to students underrepresented in STEM,” said Brown. “The way we want to do this is by first lighting the fires of inspiration, and then clearing the barriers to entry. Inspiration, exploration, access and inclusion.”

Space is a growing $425 billion industry. The partners on this project include the Keystone Space Collaborative, the Readiness Institute at Penn State, Discovery Space of Central Pennsylvania, as well as the Moonshot Museum, Carnegie Science Center and Astrobotic.

“Astrobotic, as a business, is all about making space accessible to the world. We are so dedicated to that, that we have gone to the next step to create the Moonshot Museum,” said John Thornton, CEO of Astrobotic.

“The big idea is that kids young and old can walk right up to the glass, see a real spacecraft being built on the other side that will be sent to the surface of the moon and deploy real sensors and robots down to the surface … You can get a front-row seat from our mission control, right up the street,” added Thornton.

The Moonshot Museum, which will be located within Astrobotic’s North Side headquarters, was started with help from a $500,000 grant from the R.K. Mellon Foundation. It will be the first museum in the state dedicated to space exploration.

During last night’s event, Pennsylvania Congressman Conor Lamb recalled when the first Soviet satellite Sputnik captured the world’s imagination and showed how far behind America was in space exploration. He said that President Kennedy was determined to reverse that, and promised to land on the Moon, at a time when more Soviet dogs had been in outer space than American astronauts.

“He says to his team, ‘Look, coming in second in the Space Race is the same as losing. There’s no second place. We have to change the game,’” said Lamb. “In a literal sense what he declared was impossible. There was no rocket capable of getting us to the Moon, no spacecraft capable of landing in 1961. But he had the instinct that if you actually set the goal … and follow it up with enough resources, America was able to meet challenges like that.”

As we all know, America rose to meet this “impossible” challenge.

“Ultimately there were 410,000 people working on the Apollo program, many with NASA but in the private sector as well,” added Lamb. “Companies like Alcoa in western Pennsylvania supplied them with over a million pounds of aluminum. Outside of war, it’s the largest single endeavor that a group of people have ever really taken a part in, until, really, the pandemic happened.”

That kind of resolve, that talent, that perseverance, is still present in Americans.

“We, the Americans of the 2010s, 2020s and 2030s, are just as capable of accomplishing something like that today, as they were in the 1960s,” said Lamb.

Pittsburgh is poised to be a place where that work happens.

“We are creating a true ecosystem, from middle school to high school all the way through college and ultimately in industry,” said Thornton. “You can live and work in space in Pittsburgh.”

The Science Center kickoff event also featured a keynote speech by Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, who detailed the recent successes in exploring Mars.

“Look at the Moon,” Zurbuchen said. “Look at it and think of all these places we’re going to go. And landers from this community will land and do amazing science.”