The Maker Movement

By Christine O’Toole

Back in 2011, the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh began to test a radical theory. What if the museum invited visitors not just to look at exhibits or touch a digital screen, but also to pick up tools and make something that works?

Arriving amid a deluge of digital experiences, the idea to reintroduce skills like circuitry, sewing and carpentry seemed decidedly retro. But it sparked a response not only in Pittsburgh, but also across the country. Three years later, the museum has become an acknowledged leader in introducing youngsters to practical hands-on learning. The museum’s MAKESHOP® project recently received a $425,000 federal grant to lead a national project, introducing the concept to institutions around the country.

With its entry into the Maker Movement, a trend toward creative do-it-yourself experimentation, the Children’s Museum is bridging the gap between the classroom and community institutions. Leaders of the local MAKESHOP effort believe that informal education can bolster school efforts to ignite curiosity and confidence in designing and creating useful physical objects, and encourage students to carry those skills into their adult careers. It’s a farsighted strategy to create the manufacturing innovators of the future.

In partnership with local researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh, the museum created prototypes to guide children along the steps from design to completion. Among the first exhibits was a simple array of circuit blocks with LED lights, motors and buzzers. Attaching the devices to a battery station allowed users to close a circuit through trial and error.

The museum began by targeting children age eight and older. But it soon found that the exhibits proved equally popular with four- and five-year-olds and adults. As museum educators worked with their university partners, they realized that visitors of all ages found the hands-on experience compelling.

“We emphasize the family as a learning unit–they’re co-learners, and also teachers,” explains Lisa Brahms. The director of learning and research at the museum, she is also a learning researcher at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Learning in Out of School Environments (UPCLOSE). “They all learn how a needle works, how a soldering iron works.” In an era when solitary, online learning is rapidly becoming the norm, MAKESHOP emphasizes collaboration–a skill that both educators and employers predict will be increasingly important in the workplace. “Making [something] highlights relationships,” she says. “You learn from others and with others. You don’t have to know everything — you use the resources of the community.”

Each child’s experience in the exhibit begins with a question: “What would you like to make today?” Children begin by sketching a design of their project. Then, using free tools and materials, such as disassembled electronics gear, felt, handlooms, clamps, sandpaper and files, they create their design with staff guidance. A sampling of recent activities includes hands-on experiences with computer programming, squishy circuits, 3-D printing, laser cutting, 3-D design challenge collaborations and MAKESHOP City, a miniature metropolis built from recycled materials.

The visitor response to MAKESHOP showed intense interest. UPCLOSE found that 64 percent of families spent from 30 minutes to two hours there, compared to six to 20 minutes at most other exhibits. Most cultural organizations are struggling to reach new audiences these days, but MAKESHOP has helped the museum expand by demand. In 2013, more than 267,025 children and families visited the museum, marking a third consecutive year of record-setting attendance numbers and a 7.5 percent increase over the previous year.

Melissa Butler spent a school year as teacher in residence at the museum, prototyping K–2 classroom activities for her students at Pittsburgh Allegheny, a nearby public school. She observed how her students and fellow teachers worked as they made weekly visits to the museum and documented the project’s connections with core curricula, such as vocabulary and language development, math, and science.

“For young children, naming and understanding materials–whether they are flexible or sturdy, whether they are attachments or connections–provides real understanding,” she says. “Among second-graders, we saw amazing connections to mathematics. One little girl was proficient in measuring length. But when she worked with wooden dowels, she didn’t realize that some were pushed higher than others–they weren’t all the same length. Students may pass a test, but when you invite them to open-ended problem-solving play, they grasp the concept differently.”

To Brahms, approaching children as makers rather than as passive learners makes old-school sense. “Institutions are looking for ways to engage kids and learning. John Dewey knew a century ago that hands-on learning with real tools and real materials and real-world situations improved productive learning. People are remembering and rethinking [the progressive educator’s] approach,” she says.

This article originally appeared in the 2013 Annual Report for the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation.

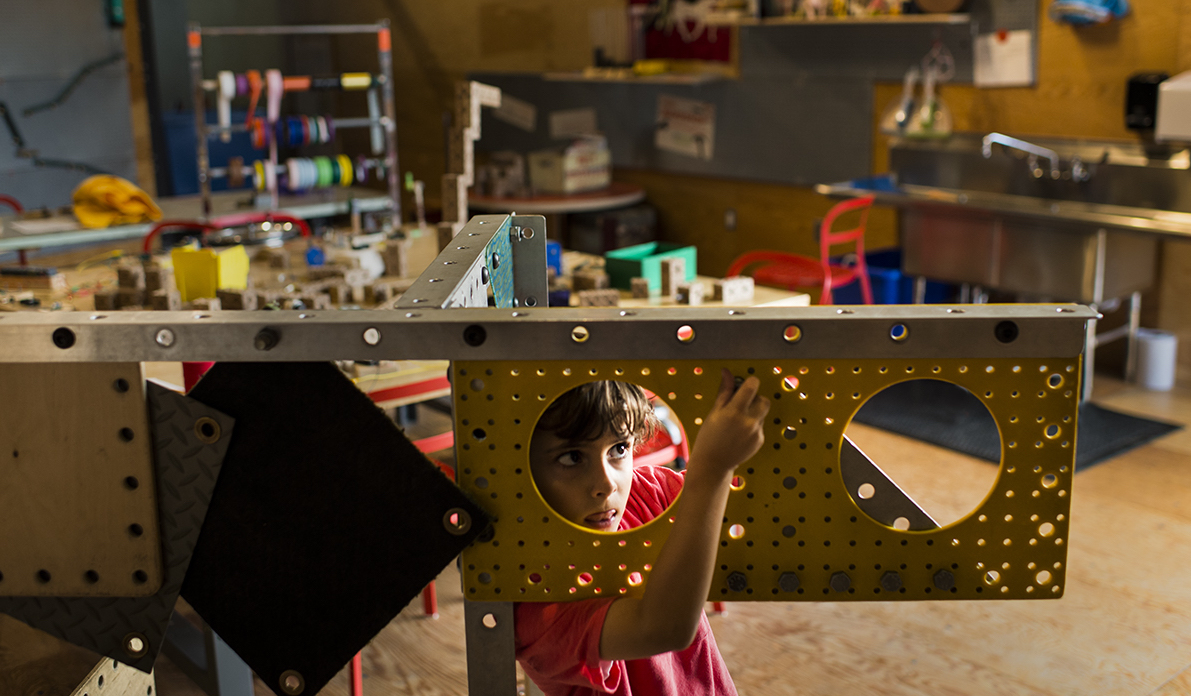

Featured Photo: Child creating in the MAKESHOP at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, Photo by Rebecca Kiger