What other schools can learn from New Castle School District

Above photo: Demetri Ruby, a junior at New Castle High School, works on a project using a hybrid material of concrete and shredded plastic.

In a former storage room in the basement of the New Castle Junior and Senior High School, 17-year-old Demetri Ruby brushes a liquid onto the surface of an oblong concrete bowl, which resembles a sink with no drain.

Ruby explains that the material is a mix of concrete and shredded plastic, a combination that he and his classmates determined has an increased R factor – or, resistance transfer factor – making it ideal to use as an insulating building material. The bowl is a cooler: Place drinks inside, even without ice, and they stay cold, he says. But the students have found other uses by making bricks out of the material, which if used in the construction of, say, a house would help stabilize inside temperatures.

“It’s pretty amazing,” says Demetri, a junior.

In this high-tech workshop – in a long-underperforming school district with kids from mostly disadvantaged homes – Demetri and other New Castle students are preparing for a future that until recently seemed unattainable.

In 2015, the New Castle Area School District received a $20,000 grant to turn five unused rooms in the school basement into hi-tech classrooms in which teachers would focus on the STEAM curriculum of science, technology, engineering, arts, and math.

Learning spaces were reimagined. New initiatives, focused on training students for 21st Century jobs, were implemented.

School officials say they can already see benefits.

“It is absolutely working,” says Emily Sanders, director of Data Assessment and Technology with the New Castle Area School District. “There’s been a paradigm shift in the way we approach teaching and learning. With new technology, teachers are able to customize and personalize lessons to meet kids at their level. And you can see (students) taking ownership of their learning.”

Consider Demetri: A couple of years ago, he had no idea what he wanted to do professionally. Then he took an engineering course in one of the new STEAM classrooms.

“I’m planning on being a civil engineer,” Demetri says. “I’m researching schools now, but I’m thinking about The Citadel.”

Before taking this class, “my plan was, I don’t know, just to go wherever life took me, I guess.”

Now he believes engineering can take him anywhere.

Traditional learning methods were not working, school officials here said, not in a district like New Castle where 100% of the district’s 3,500 students qualify for free and reduced-price lunches, and a backpack program every Friday sends 400 kids home with the only food they may eat all weekend.

It’s too soon to tell whether the new initiatives are impacting test scores, which remain well below state norms, officials say, but anecdotal evidence suggests a more engaged student body: Absentee rates are down, as are disciplinary referrals.

“You want kids to enjoy school, and now you see it on their faces: They do,” says Tabitha Marino, co-principal of George Washington Intermediate school.

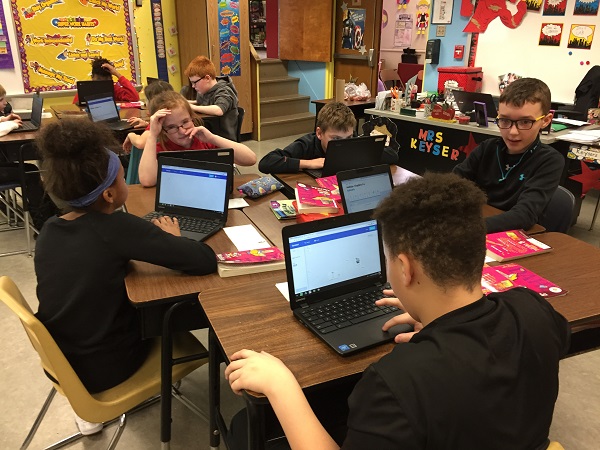

At Marino’s school, kids begin learning to code in kindergarten, and a new initiative called 1:1 has paired all 250 fifth-graders with their own Google Chromebooks.

“Before, we’d approach learning in an up and down way, with the teacher standing in front of the room, students sitting in rows of chairs, and the teacher shouting something out in hopes that all 25 students got it,” says Doug Englehart, a fifth-grade math and science teacher. “When five don’t understand, the teacher approaches them to help, and the other 20 are sitting there with nothing to do.”

Now, he says, he can break students into groups, each of whom has a lesson specifically designed for them on their Chromebooks.

“I’m always asking, ‘How am I going to reach everybody?’ ” Englehart says. “This allows us to individually instruct students without leaving anyone behind. I can keep them all engaged and focus in on the two or three that need help. I love that.”

On this day, students are clustered in groups in Englehart’s class as they tackle tasks. One group identifies geometric shapes and then learns their practical applications. Another group uses their coding skills to create an image of their names, blinking and glowing, over a photo of a picnic table. Some students sit at tables, while others form a small circle on the floor.

The classes are visually different from what students’ parents experienced.

But officials say they’ve felt little pushback.

“The key is to educate parents along the way,” Englehart says. “Once they see it, they get it.’”

Of course, there was some pushback – from within the school district itself.

When Sanders announced the bright colors she envisioned for the STEAM classrooms, for instance, the high school principal balked. Later, she says, custodians flatly refused to use the paint she bought because the colors were so non-traditional.

In time, they came around. Others are, too.

English teacher Andrea Keyser – who is in her 25th year teaching at the school – says she feels like “a brand-new teacher.”

“I can’t wait to come to school and show them something new,” she says.

As her students silently work on their Chrome Books, Sanders notes that this group is known for having discipline problems.

On this day, however, they are silent and focused on their work.